Interstitial Cystitis and Bladder Pain Syndrome

Interstitial Cystitis and Bladder Pain Syndrome

Last Section Update: 03/2023

Contributor(s): Maureen Williams, ND; Shayna Sandhaus, PhD

1 What is Interstitial Cystitis and Bladder Pain Syndrome?

Summary and Quick Facts

- Interstitial cystitis, sometimes called bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS), is a disorder that causes bladder pain and urinary urgency.

- The cause of IC/BPS is not known, but several factors that might contribute have been identified.

- Dietary and lifestyle changes, like avoiding spicy foods, alcohol, and caffeine, as well as bladder-training techniques, may provide relief for some people.

- Evidence suggests that several nutrients, such as L-arginine, quercetin, and probiotics, may reduce symptoms in some cases.

- Several medical treatments, including drugs and procedures, are available, but often not very effective. Many patients have to try several therapies before finding an approach that provides relief.

“Interstitial cystitis” and “bladder pain syndrome” (IC/BPS) are terms used to describe chronic bladder pain or pressure along with urinary symptoms such as urgency, frequency, and sleep disruption due to the need to urinate.2,3 These symptoms can have a profound negative impact on emotional and social well-being and quality of life.4,5 Symptoms may wax and wane, with “flares” interspersed among periods when symptoms are less bothersome.7

To diagnose IC/BPS, doctors first rule out other possible causes of bladder symptoms. Findings from physical exam and medical history, urine and blood tests, and cystoscopy (a procedure to visualize the inside of the bladder and urethra) are used to rule out other possible causes and check for bladder abnormalities.2

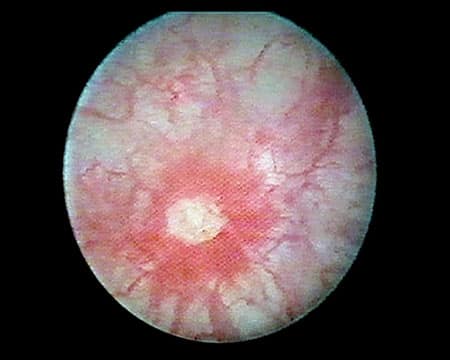

Although symptoms of IC/BPS overlap with those of urinary tract infection (UTI), individuals with IC/BPS do not show clear signs of infection and generally do not improve with antibiotics. In fact, the absence of any identifiable cause is a diagnostic hallmark of IC/BPS.2,5,8 Ulcers on the bladder wall, called Hunner lesions (Figure 1), are present in about 5–10% of cases of IC/BPS, although it is possible that they are under-diagnosed and are present in up to half of all IC/BPS cases.9-11 As cystoscopy is not required for diagnosis, these lesions may be present yet not identified. Evidence suggests their presence indicates a distinct condition, or at least a more-clearly delineated subtype of IC/BPS.9,10

2 What Causes Interstitial Cystitis and Bladder Pain Syndrome?

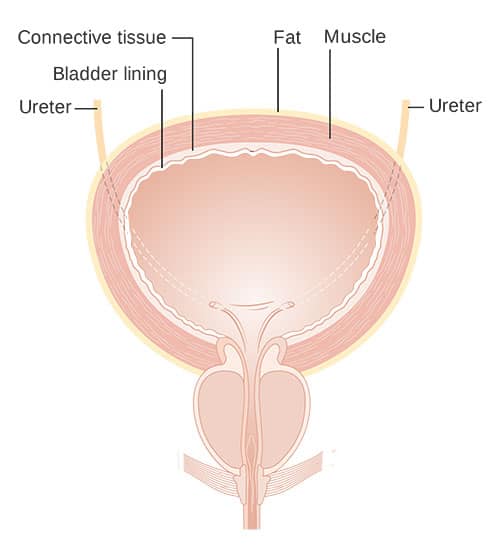

The cause of IC/BPS is unknown. Changes in the sensory and barrier functions of the cells lining the bladder (Figure 2) are thought to play a role. The specialized cells that make up the inner bladder wall are responsible for protecting underlying muscles, nerves, blood vessels, and connective tissue from exposure to excess water, toxins, microbes, and various other compounds present in the urine. They also communicate with sensory nerves within the bladder wall.5

Changes in the structure and composition of the bladder lining have been observed in patients with IC/BPS. These changes may disrupt barrier function and alter sensory signaling, triggering symptoms including urinary urgency and pain.5

Immune system irregularities (eg, autoimmunity, chronic inflammation), undetected chronic infection, inflammation and/or hyperexcitability of the bladder nerves, and altered signaling between the bladder and other pelvic tissues may also contribute.2,5

Although most studies suggest that IC/BPS is more common in women, some research shows it may occur almost as frequently in men.5,12

IC/BPS frequently co-occurs with other chronic disorders, including fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and anxiety.5,12 IC/BPS can be an underlying cause of chronic pelvic pain, often along with other conditions associated with pelvic pain, such as endometriosis, pelvic adhesions, and irritable bowel syndrome.13 In men, IC/BPS has a high level of overlap with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome.8 Chronic stress has been linked to both the development and worsening of IC/BPS symptoms.14 Other studies have shown increased sympathetic (“fight or flight”) and decreased parasympathetic (relaxed) nervous system activation in patients with IC/BPS.5

Some IC/BPS sufferers note that certain foods and activities can worsen their symptoms. Commonly reported triggers include spicy foods, citrus fruits, tomatoes, chocolate, caffeinated drinks, alcohol, artificial sweeteners, overexertion, prolonged sitting, exercises that work the abdominal muscles (eg, sit-ups and crunches), riding a bicycle or horse, sexual activity, and wearing tight clothing.7,15

3 Nutrients

L-arginine

L-arginine, an amino acid made in the body and found in protein-containing foods, is used to make nitric oxide, a messenger molecule with many functions including regulating fluid balance, muscle tone, nerve excitability, and immune activity.16 Lower levels of nitric oxide synthase activity have been shown in the urine of patients with IC/BPS.17 Randomized placebo-controlled trials have noted L-arginine, at doses of 1.5–2.4 grams per day, led to a small but significant positive impact on symptoms in some patients with IC/BPS. Two open-label uncontrolled trials found 1.5 grams L-arginine daily for six months increased urinary nitric oxide synthase activity and reduced IC/BPS symptoms.17,18 However, in one report, no positive effects were seen in nine IC/BPS patients given either 3 grams or 10 grams of L-arginine per day five weeks.19

Chondroitin Sulfate/Glucosamine Sulfate/Hyaluronic Acid

Chondroitin sulfate, glucosamine sulfate, and hyaluronic acid are glycosaminoglycan molecules that contribute to the protective barrier of the bladder lining.20 Although most research has focused on intravesical (administered directly into the bladder) use of these compounds, one uncontrolled trial in 252 subjects with IC/BPS found treatment with an oral supplement providing 600 mg chondroitin sulfate, 480 mg glucosamine sulfate, and 40 mg hyaluronic acid, plus 600 mg quercetin and 80 mg rutin (anti-inflammatory flavonoids), per day led to reduced symptom severity during more than 12 months of monitoring and was more effective in those who had more severe symptoms at the beginning of the trial.21 Another small open trial with 37 participants also found this combination reduced IC/BPS symptom severity after six months.22

French Maritime Pine Bark

A standardized extract from French maritime pine bark known as Pycnogenol was tested for its effects in an open clinical trial that included 64 participants with recurrent urinary tract infections or interstitial cystitis. The participants were treated with standard therapies alone or with 150 mg Pycnogenol or 400 mg cranberry extract daily for 60 days. Both Pycnogenol and cranberry extract reduced the rate of infections more than standard therapies alone, and Pycnogenol was more effective than cranberry extract. The likelihood of being symptom-free at the end of the trial was highest in the Pycnogenol group.23 Because cranberry can be a food that triggers symptoms in some individuals with IC/BPS, this may have been a factor in Pycnogenol performing better overall in this population.15

Quercetin

Quercetin is a flavonoid found widely in plant foods that has anti-inflammatory effects in the body. In particular, quercetin inhibits activation of mast cells (ie, immune cells that release histamine as part of the inflammatory immune response).24 Mast cells have been implicated as being a specific contributor to IC/BPS symptoms.25 In an uncontrolled open trial, treatment with 500 mg quercetin twice daily for four weeks led to improvement in three different measures of IC/BPS symptoms.26

Palmitoylethanolamide

Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) is a fatty acid derivative that may regulate the endocannabinoid system affecting inflammation and pain. In an open uncontrolled trial, 32 IC/BPS patients were treated with 400 mg micronized PEA plus 40 mg polydatin (a naturally occurring precursor to the polyphenol resveratrol) twice daily for three months followed by once daily for three months. Progressive reductions in pain and urinary frequency, as well as overall symptom severity, were noted.27

N-acetylcysteine

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is a sulfur-containing amino acid compound that raises levels of glutathione, an important free radical scavenger. NAC is used clinically to help clear mucus, prevent fibrosis in the lungs, and enhance detoxification pathways in the liver.28 It also has many uses in the mental health setting.29,30 In a rat model of IC/BPS, NAC injections reduced bladder wall injury and fibrosis and improved normal bladder function.31 Intravenous NAC therapy was reported to lead to complete remission in the case of a patient with IC/BPS for 26 years despite treatment with multiple therapies, but more studies are needed before IV NAC can be recommended as a therapy for IC/BPS.32

Melatonin

Melatonin, which is best known for its role in regulating the body’s circadian clock, is also an important oxidative stress-reducing hormone. Animal research suggests melatonin may protect the bladder lining by limiting free radical injury, reducing inflammatory cytokine levels, decreasing mast cell proliferation, and inhibiting pain signaling.33,34

Magnesium

Magnesium deficiency can cause inflammation of nerves and aggravate pain. In a rat model of IC/BPS, magnesium L-threonate (a form of magnesium that crosses the blood‒brain barrier) reduced signs of pain hypersensitivity and depressive behaviors.35

Probiotics

Once thought to be sterile, the healthy urinary system has recently been recognized as having a microbial ecosystem. Composition of the urinary microbiome has been found to be altered in urinary disorders, including IC/BPS.36,37 A disruption in normal microbial balance affects immune function, inflammatory signaling, and even transmission of pain signals.38 A report on two cases suggests a probiotic supplement (in one case described as providing at least 2 billion viable cells per day of a mix of Lactobacillus rhamnosus, L. acidophilus, L. bulgaricus, Streptococcus thermophilus, and Bifidobacterium bifidum) may be helpful as part of a comprehensive approach to treating IC/BPS, particularly in those with a history of recurrent UTI and repeated courses of antibiotics.39 Interestingly, mindfulness-based stress reduction techniques in individuals with IC/BPS were shown to alter the urinary microbiome, increasing diversity, along with an improvement in symptoms in a small study.40

Horsetail, Three-leaf Caper, and Lindera

Horsetail (Equisetum arvense), three-leaf caper (Crataeva nurvala), and lindera (Lindera aggregata) have been used historically to support urinary and bladder health.68,69 In a rat model of overactive bladder, an herbal extract combination of these ingredients improved bladder function and levels of biomarkers associated with bladder overactivity.70 This combination was evaluated in a placebo-controlled trial that included 88 women given 840 mg of the herbal blend or placebo once daily for eight weeks. Compared with placebo, those given the herbal extract had their urinary frequency normalized and experienced a significant reduction in episodes of incontinence, urinary urgency, and nocturia.69

4 Dietary and Lifestyle Considerations

Given the lack of consistently effective medical/drug-based therapies for IC/BPS, diet and lifestyle approaches are important first-line strategies for managing the condition. For many people with IC/BPS, avoiding recognized triggers and practicing other self-care measures are sufficient for managing symptoms; however, in the majority of cases, additional therapies are needed.2

Diet

Identifying and avoiding foods that trigger symptoms can be helpful for many IC/BPS patients. More than 80% of patients report dietary sensitivity to certain foods.2 In one recent survey, 48 of 51 participants (94.1%) identified at least one food trigger and the average number of food triggers reported was 7.5.15 Alcohol, caffeine, chocolate, tomatoes, citrus, spicy foods, and carbonated drinks are among the most frequent dietary triggers.2,4 Others include pineapple, cranberries, vinegar, yogurt, and onions.15

An elimination diet followed by systematic food re-introductions can be useful for determining which foods exacerbate symptoms and trigger flares in individuals with IC/BPS. This approach can also be helpful for detecting food sensitivities that contribute to co-occurring pain conditions such as fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome.41

Bladder Training

Controlling fluid intake and timing urination to gradually prolong the time interval between urinating are strategies that benefit some individuals with IC/BPS.2,10

Pelvic Floor Therapies

Clinical trials have found pelvic floor exercises and biofeedback training can help reduce urinary frequency in IC/BPS patients. In one controlled trial in 123 women with IC/BPS, a biofeedback and pelvic floor muscle training program was found to enhance the effectiveness of medical therapies.42 Pelvic floor muscle massage and trigger point therapy, which can be self-administered with training, have been shown to help those with signs of pelvic floor dysfunction.2,10

Psychosocial Interventions

Education and support are important but underappreciated aspects of treatment.43 One small uncontrolled study in 12 IC/BPS patients found an eight-week mindfulness-based stress reduction program improved symptoms.40 Resources for support include:

5 Medical Treatment of Interstitial Cystitis and Bladder Pain Syndrome

A number of approaches are used to treat IC/BPS, but none are consistently and definitively effective in all patients.44 Medical treatments include oral, intravesical (administered by catheter directly into the bladder), and injected therapies targeting improved barrier function, reduced hypersensitivity, and decreased inflammation.45 The treatments your doctor suggests will depend on his or her clinical experience with IC/BPS, as there is little robust scientific evidence supporting specific treatment approaches for all patients. Many patients will need to try a few different treatment options to find one that provides some relief.

Oral Treatments

Pentosan polysulfate sodium. Oral pentosan polysulfate sodium (Elmiron), a semisynthetic material thought to work by acting as a protective barrier, is the only FDA-approved oral treatment for IC/BPS. Nevertheless, it has demonstrated only marginal effectiveness and is associated with adverse side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and hair loss; it may also increase risk of certain eye diseases.10,46 Additionally, it has been shown symptom improvement may not occur for three to six months after beginning treatment, a timeline which is not acceptable for many.47

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Over-the-counter and prescription non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen (Advil) and naproxen (Aleve) can provide short-term pain relief in some patients with IC/BPS.44 However, long-term use of NSAIDs increase risk of gastric bleeding, cardiovascular events, and kidney and liver damage.48

Amitriptyline and gabapentin. Amitriptyline (Elavil, an antidepressant) and gabapentin (Neurontin, an anti-seizure medication) are used to treat neuropathic pain and have shown limited efficacy in people with IC/BPS.49 These drugs are associated with several side effects, which may be dose-limiting in some cases.10,50

Antihistamines. Cimetidine (Tagamet), a histamine H2 antagonist used to treat acid reflux and heartburn, was found in one small randomized controlled trial to improve pain and sleep disruption in IC/BPS sufferers.51 Evidence for hydroxyzine (Atarax, Vistaril), a histamine H1 antagonist, is mixed, with some research suggesting it may improve the effects of pentosan polysulfate sodium.2 These medications are generally safe and well tolerated, though sedation is a frequent side effect of hydroxyzine.10

Cyclosporin A. Cyclosporin A (Gengraf) is an anti-inflammatory immunosuppressant that has been shown to benefit some patients with otherwise unresponsive symptoms. The response has been shown to be better in those known to have Hunner lesions.52 Because of its potential to cause serious adverse side effects, cyclosporin A is reserved for those with intractable symptoms.2,10

Intravesical Treatments

Dimethyl sulfoxide. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) is an agent with anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and muscle-relaxing effects and is the only FDA-approved intravesical therapy for IC/BPS. Its use is reported to result in improvement in up to 95% of patients and is especially beneficial in those with Hunner lesions; however, more than 35% of patients experienced relapse within eight weeks. Many patients cannot tolerate the pain and garlic-like odor associated with this treatment.10

Glycosaminoglycans. Intravesical glycosaminoglycan therapies, including chondroitin sulfate, hyaluronic acid, heparin sulfate, and pentosan polysulfate sodium, are intended to protect the bladder wall and improve barrier function. They are typically used in combination with analgesics. Limited randomized controlled trials suggest these therapies may be beneficial and have similar response rates.2 Improvements of up to 85% have been seen with intravesical hyaluronic acid.53

Lidocaine and bupivacaine. Lidocaine and bupivacaine (Marcaine) are anesthetics used intravesically for IC/BPS. A five-day course of treatment with lidocaine has been found to reduce symptoms even after the end of treatment.54

Intravesical cocktails that include an anesthetic, a glycosaminoglycan, sodium bicarbonate (as an alkalinizing agent), and sometimes an antibiotic and/or corticosteroid appear to be more beneficial than single therapies.2

Bladder Injections

Botulinum toxin type A (Botox). Botulinum toxin type A (Botox) is a neurotoxin used in low-dose injections to quiet muscular over-activity. Clinical trials have shown injections of botulinum toxin into the muscular bladder wall can effectively inhibit muscle and nerve hypersensitivity, reduce inflammation, and relieve some symptoms of IC/BPS.55,56 Improvements with botox injections alone diminish over time, with positive effects lasting approximately five months.2 An important potential adverse effect is dysfunction of the bladder muscle, leading to decreased ability to empty the bladder, increased risk of UTI, and need for periodic catheterization.10,56

Regenerative Therapies

Regenerative approaches to IC/BPS have gained attention in recent years. These strategies are aimed at promoting tissue repair, and preclinical and preliminary clinical evidence suggests they may improve measures of IC/BPS symptoms and bladder function.

Platelet-rich plasma. Blood plasma is a cell-free, liquid component of blood. It is mostly water but also transports proteins, growth factors, glucose, and other biological factors, including platelets, which are involved in blood clotting. Platelet-rich plasma contains more platelets than normal and is obtained by centrifuging plasma to concentrate the platelets, growth factors, and other compounds to about 2–5 times baseline concentrations. Injections of platelet-rich plasma have therapeutic potential that is being applied in several areas of medicine. Administration of platelet-rich plasma (eg, via injection) promotes local cellular changes that may be beneficial under certain circumstances.57,58

Preliminary evidence suggests platelet-rich plasma may have therapeutic value in IC/BPS. In two small trials, one involving 15 subjects and the other 40 subjects, monthly intravesical injections of platelet-rich plasma led to improvements in some symptoms and aspects of bladder function. These trials also demonstrated the safety of platelet-rich plasma injections in this context.59,60 Larger controlled trials are needed to clarify the therapeutic value of platelet-rich plasma in people with IC/BPS.

Mesenchymal stem cell therapy. Mesenchymal stem cells are adult stem cells, found predominantly in adipose (fat), cartilage, and bone tissue, that have an important role in connective tissue repair and regeneration due to their ability to differentiate into multiple types of cells, depending on the signals they receive. Emerging research suggests mesenchymal stem cells have potential benefits in treating a range of degenerative disorders, including some neurological, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal conditions.61 In a rat model of IC/BPS, injecting adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells into the bladder wall reduced the number of mast cells, collagen activation leading to fibrosis, hypersensitivity to pain, and over-activity of bladder musculature.62Systemic Injection

Certolizumab pegol. Certolizumab pegol (Cimzia), a monoclonal antibody used to treat autoimmune diseases, is being investigated for its possible benefits in interstitial cystitis.65 It is administered by subcutaneous injections.44,66

Other Approaches

As many as 90% of patients with Hunner lesions have been reported to benefit from topical treatments or procedures that remove or destroy the ulcerated tissue.10 Improvements with this are fairly longstanding, although many found the need to repeat the procedure after two to five years.

Hydrodistention, in which the bladder wall is stretched by an infusion of saline while the patient is anesthetized, has been reported to relieve symptoms in 30–55% of cases, but often needs to be repeated and carries the risk of complications such as rupture and necrosis. Therefore, it is generally reserved for those who do not respond to other medical therapies.10

A number of small studies have indicated implantable devices that modulate the activity of the sacral nerves may reduce symptoms in some IC/BPS patients, but about half of patients treated with these devices need to have them removed due to lack of effect or uncomfortable side effects.10

Finally, major surgery (eg, removal or replacement of all or part of the bladder, and/or rerouting of the urinary stream) can be effective but has a high complication rate and is a last option for those with severe, debilitating, intractable symptoms.2,67

Disclaimer and Safety Information

This information (and any accompanying material) is not intended to replace the attention or advice of a physician or other qualified health care professional. Anyone who wishes to embark on any dietary, drug, exercise, or other lifestyle change intended to prevent or treat a specific disease or condition should first consult with and seek clearance from a physician or other qualified health care professional. Pregnant women in particular should seek the advice of a physician before using any protocol listed on this website. The protocols described on this website are for adults only, unless otherwise specified. Product labels may contain important safety information and the most recent product information provided by the product manufacturers should be carefully reviewed prior to use to verify the dose, administration, and contraindications. National, state, and local laws may vary regarding the use and application of many of the therapies discussed. The reader assumes the risk of any injuries. The authors and publishers, their affiliates and assigns are not liable for any injury and/or damage to persons arising from this protocol and expressly disclaim responsibility for any adverse effects resulting from the use of the information contained herein.

The protocols raise many issues that are subject to change as new data emerge. None of our suggested protocol regimens can guarantee health benefits. Life Extension has not performed independent verification of the data contained in the referenced materials, and expressly disclaims responsibility for any error in the literature.

- Cancer Research UK. Diagram showing the layers of the bladder. Accessed 08/16/2021, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Diagram_showing_the_layers_of_the_bladder_CRUK_304.svg

- Colemeadow J, Sahai A, Malde S. Clinical Management of Bladder Pain Syndrome/Interstitial Cystitis: A Review on Current Recommendations and Emerging Treatment Options. Research and reports in urology. 2020;12:331-343. doi:10.2147/RRU.S238746

- Homma Y. Interstitial cystitis, bladder pain syndrome, hypersensitive bladder, and interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome - clarification of definitions and relationships. Int J Urol. Jun 2019;26 Suppl 1:20-24. doi:10.1111/iju.13970

- Lim Y, O'Rourke S. Interstitial Cystitis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2021, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2021.

- Birder LA. Pathophysiology of interstitial cystitis. Int J Urol. Jun 2019;26 Suppl 1:12-15. doi:10.1111/iju.13985

- Persu C, Cauni V, Gutue S, Blaj I, Jinga V, Geavlete P. From interstitial cystitis to chronic pelvic pain. J Med Life. Apr-Jun 2010;3(2):167-74.

- Quentin Clemens J. Patient Education: Treatment of Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome. . UpToDate. 2019;

- Marcu I, Campian EC, Tu FF. Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome. Seminars in reproductive medicine. Mar 2018;36(2):123-135. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1676089

- Akiyama Y, Homma Y, Maeda D. Pathology and terminology of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: A review. Histology and histopathology. Jan 2019;34(1):25-32. doi:10.14670/HH-18-028

- Garzon S, Lagana AS, Casarin J, et al. An update on treatment options for interstitial cystitis. Przeglad menopauzalny = Menopause review. Mar 2020;19(1):35-43. doi:10.5114/pm.2020.95334

- Whitmore KE, Fall M, Sengiku A, Tomoe H, Logadottir Y, Kim YH. Hunner lesion versus non-Hunner lesion interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. Int J Urol. Jun 2019;26 Suppl 1:26-34. doi:10.1111/iju.13971

- Chang KM, Lee MH, Lin HH, Wu SL, Wu HC. Does irritable bowel syndrome increase the risk of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome? A cohort study of long term follow-up. Int Urogynecol J. May 2021;32(5):1307-1312. doi:10.1007/s00192-021-04711-3

- Speer LM, Mushkbar S, Erbele T. Chronic Pelvic Pain in Women. American family physician. Mar 1 2016;93(5):380-7.

- Komesu YM, Petersen TR, Krantz TE, et al. Adverse Childhood Experiences in Women With Overactive Bladder or Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. Jan 1 2021;27(1):e208-e214. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000894

- Lai HH, Vetter J, Song J, Andriole GL, Colditz GA, Sutcliffe S. Management of Symptom Flares and Patient-reported Flare Triggers in Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome (IC/BPS)-Findings From One Site of the MAPP Research Network. Urology. Apr 2019;126:24-33. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2019.01.012

- Appleton J. Arginine: Clinical potential of a semi-essential amino acid. Alternative medicine review : a journal of clinical therapeutic. Dec 2002;7(6):512-22.

- Wheeler MA, Smith SD, Saito N, Foster HE, Jr., Weiss RM. Effect of long-term oral L-arginine on the nitric oxide synthase pathway in the urine from patients with interstitial cystitis. J Urol. Dec 1997;158(6):2045-50. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(01)68150-3

- Smith SD, Wheeler MA, Foster HE, Jr., Weiss RM. Improvement in interstitial cystitis symptom scores during treatment with oral L-arginine. J Urol. Sep 1997;158(3 Pt 1):703-8. doi:10.1097/00005392-199709000-00005

- Ehren I, Lundberg JO, Adolfsson J, Wiklund NP. Effects of L-arginine treatment on symptoms and bladder nitric oxide levels in patients with interstitial cystitis. Urology. Dec 1998;52(6):1026-9. doi:10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00343-4

- Cervigni M. Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and glycosaminoglycans replacement therapy. Transl Androl Urol. Dec 2015;4(6):638-42. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2015.11.04

- Theoharides TC, Kempuraj D, Vakali S, Sant GR. Treatment of refractory interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome with CystoProtek--an oral multi-agent natural supplement. The Canadian journal of urology. Dec 2008;15(6):4410-4.

- Theoharides TC, Sant GR. A pilot open label study of Cystoprotek in interstitial cystitis. International journal of immunopathology and pharmacology. Jan-Mar 2005;18(1):183-8. doi:10.1177/039463200501800119

- Ledda A, Hu S, Cesarone MR, et al. Pycnogenol® Supplementation Prevents Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections/Inflammation and Interstitial Cystitis. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM. 2021;2021:9976299. doi:10.1155/2021/9976299

- Weng Z, Zhang B, Asadi S, et al. Quercetin is more effective than cromolyn in blocking human mast cell cytokine release and inhibits contact dermatitis and photosensitivity in humans. PloS one. 2012;7(3):e33805.

- Liu H-T, Shie J-H, Chen S-H, Wang Y-S, Kuo H-C. Differences in mast cell infiltration, E-cadherin, and zonula occludens-1 expression between patients with overactive bladder and interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. Urology. 2012;80(1):225. e13-225. e18.

- Katske F, Shoskes DA, Sender M, Poliakin R, Gagliano K, Rajfer J. Treatment of interstitial cystitis with a quercetin supplement. Tech Urol. Mar 2001;7(1):44-6.

- Cervigni M, Nasta L, Schievano C, Lampropoulou N, Ostardo E. Micronized Palmitoylethanolamide-Polydatin Reduces the Painful Symptomatology in Patients with Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:9828397. doi:10.1155/2019/9828397

- Kelly GS. Clinical applications of N-acetylcysteine. Alternative medicine review : a journal of clinical therapeutic. Apr 1998;3(2):114-27.

- Fernandes BS, Dean OM, Dodd S, Malhi GS, Berk M. N-Acetylcysteine in depressive symptoms and functionality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2016;77(4):0-0.

- Paydary K, Akamaloo A, Ahmadipour A, Pishgar F, Emamzadehfard S, Akhondzadeh S. N‐acetylcysteine augmentation therapy for moderate‐to‐severe obsessive–compulsive disorder: Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Journal of clinical pharmacy and therapeutics. 2016;41(2):214-219.

- Ryu CM, Shin JH, Yu HY, et al. N-acetylcysteine prevents bladder tissue fibrosis in a lipopolysaccharide-induced cystitis rat model. Sci Rep. May 31 2019;9(1):8134. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-44631-3

- Maharaj D, Srinivasan G, Makepeace S, Hickey CJ, Gouvea J. Clinical Remission Using Personalized Low-Dose Intravenous Infusions of N-acetylcysteine with Minimal Toxicities for Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome. J Pers Med. Apr 24 2021;11(5)doi:10.3390/jpm11050342

- Cetinel S, Ercan F, Sirvanci S, et al. The ameliorating effect of melatonin on protamine sulfate induced bladder injury and its relationship to interstitial cystitis. J Urol. Apr 2003;169(4):1564-8. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000049649.80549.17

- Zhang QH, Zhou ZS, Lu GS, Song B, Guo JX. Melatonin improves bladder symptoms and may ameliorate bladder damage via increasing HO-1 in rats. Inflammation. Jun 2013;36(3):651-7. doi:10.1007/s10753-012-9588-5

- Chen JL, Zhou X, Liu BL, et al. Normalization of magnesium deficiency attenuated mechanical allodynia, depressive-like behaviors, and memory deficits associated with cyclophosphamide-induced cystitis by inhibiting TNF-alpha/NF-kappaB signaling in female rats. Journal of neuroinflammation. Apr 2 2020;17(1):99. doi:10.1186/s12974-020-01786-5

- Aragon IM, Herrera-Imbroda B, Queipo-Ortuno MI, et al. The Urinary Tract Microbiome in Health and Disease. European urology focus. Jan 2018;4(1):128-138. doi:10.1016/j.euf.2016.11.001

- Hiergeist A, Gessner A. Clinical implications of the microbiome in urinary tract diseases. Current opinion in urology. Mar 2017;27(2):93-98. doi:10.1097/MOU.0000000000000367

- Defaye M, Gervason S, Altier C, et al. Microbiota: a novel regulator of pain. Journal of neural transmission (Vienna, Austria : 1996). Apr 2020;127(4):445-465. doi:10.1007/s00702-019-02083-z

- Mansour A, Hariri E, Shelh S, Irani R, Mroueh M. Efficient and cost-effective alternative treatment for recurrent urinary tract infections and interstitial cystitis in women: a two-case report. Case Rep Med. 2014;2014:698758. doi:10.1155/2014/698758

- Shatkin-Margolis A, White J, Jedlicka AE, et al. The effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the urinary microbiome in interstitial cystitis. Int Urogynecol J. May 15 2021;doi:10.1007/s00192-021-04812-z

- Friedlander JI, Shorter B, Moldwin RM. Diet and its role in interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) and comorbid conditions. BJU Int. Jun 2012;109(11):1584-91. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10860.x

- Borrego-Jimenez PS, Flores-Fraile J, Padilla-Fernandez BY, et al. Improvement in Quality of Life with Pelvic Floor Muscle Training and Biofeedback in Patients with Painful Bladder Syndrome/Interstitial Cystitis. J Clin Med. Feb 19 2021;10(4)doi:10.3390/jcm10040862

- Windgassen S, McKernan L. Cognition, Emotion, and the Bladder: Psychosocial Factors in bladder pain syndrome and interstitial cystitis (BPS/IC). Current bladder dysfunction reports. Mar 2020;15(1):9-14. doi:10.1007/s11884-019-00571-2

- Imamura M, Scott NW, Wallace SA, et al. Interventions for treating people with symptoms of bladder pain syndrome: a network meta-analysis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Jul 30 2020;7(7):CD013325. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013325.pub2

- Chen PY, Lee WC, Chuang YC. Comparative safety review of current pharmacological treatments for interstitial cystitis/ bladder pain syndrome. Expert opinion on drug safety. May 19 2021:1-11. doi:10.1080/14740338.2021.1921733

- Lindeke-Myers A, Hanif AM, Jain N. Pentosan polysulfate maculopathy. Surv Ophthalmol. May 14 2021;doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2021.05.005

- van Ophoven A, Vonde K, Koch W, Auerbach G, Maag KP. Efficacy of pentosan polysulfate for the treatment of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: results of a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Curr Med Res Opin. Sep 2019;35(9):1495-1503. doi:10.1080/03007995.2019.1586401

- Ghlichloo I, Gerriets V. Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs). StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2021, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2021.

- Hansen HC. Interstitial cystitis and the potential role of gabapentin. Southern medical journal. 2000;93(2):238-242.

- Quintero GC. Review about gabapentin misuse, interactions, contraindications and side effects. Journal of experimental pharmacology. 2017;9:13-21. doi:10.2147/JEP.S124391

- Thilagarajah R, Witherow RO, Walker MM. Oral cimetidine gives effective symptom relief in painful bladder disease: a prospective, randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. BJU Int. Feb 2001;87(3):207-12. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02031.x

- Forrest JB, Payne CK, Erickson DR. Cyclosporine A for refractory interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: experience of 3 tertiary centers. J Urol. Oct 2012;188(4):1186-91. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2012.06.023

- Riedl CR, Engelhardt PF, Daha KL, Morakis N, Pflüger H. Hyaluronan treatment of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. May 2008;19(5):717-21. doi:10.1007/s00192-007-0515-5

- Nickel JC, Moldwin R, Lee S, Davis EL, Henry RA, Wyllie MG. Intravesical alkalinized lidocaine (PSD597) offers sustained relief from symptoms of interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome. BJU Int. Apr 2009;103(7):910-8. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08162.x

- Dan Spinu A, Gabriel Bratu O, Cristina Diaconu C, et al. Botulinum toxin in low urinary tract disorders - over 30 years of practice (Review). Experimental and therapeutic medicine. Jul 2020;20(1):117-120. doi:10.3892/etm.2020.8664

- Chen JL, Kuo HC. Clinical application of intravesical botulinum toxin type A for overactive bladder and interstitial cystitis. Investigative and clinical urology. Feb 2020;61(Suppl 1):S33-S42. doi:10.4111/icu.2020.61.S1.S33

- Alves R, Grimalt R. A Review of Platelet-Rich Plasma: History, Biology, Mechanism of Action, and Classification. Skin Appendage Disord. Jan 2018;4(1):18-24. doi:10.1159/000477353

- Lin C-C, Huang Y-C, Lee W-C, Chuang Y-C. New Frontiers or the Treatment of Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome - Focused on Stem Cells, Platelet-Rich Plasma, and Low-Energy Shock Wave. International neurourology journal. 2020;24(3):211-221. doi:10.5213/inj.2040104.052

- Jhang JF, Wu SY, Lin TY, Kuo HC. Repeated intravesical injections of platelet-rich plasma are effective in the treatment of interstitial cystitis: a case control pilot study. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. Apr 2019;11(2):O42-O47. doi:10.1111/luts.12212

- Jhang JF, Lin TY, Kuo HC. Intravesical injections of platelet-rich plasma is effective and safe in treatment of interstitial cystitis refractory to conventional treatment-A prospective clinical trial. Neurourology and urodynamics. Feb 2019;38(2):703-709. doi:10.1002/nau.23898

- Hmadcha A, Martin-Montalvo A, Gauthier BR, Soria B, Capilla-Gonzalez V. Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Cancer Therapy. Review. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020-February-05 2020;8(43):43. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2020.00043

- Furuta A, Yamamoto T, Igarashi T, Suzuki Y, Egawa S, Yoshimura N. Bladder wall injection of mesenchymal stem cells ameliorates bladder inflammation, overactivity, and nociception in a chemically induced interstitial cystitis-like rat model. Int Urogynecol J. Nov 2018;29(11):1615-1622. doi:10.1007/s00192-018-3592-8

- Shin JH, Ryu CM, Ju H, et al. Synergistic Effects of N-Acetylcysteine and Mesenchymal Stem Cell in a Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Interstitial Cystitis Rat Model. Cells. Dec 29 2019;9(1)doi:10.3390/cells9010086

- Chen YT, Chiang HJ, Chen CH, et al. Melatonin treatment further improves adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell therapy for acute interstitial cystitis in rat. Journal of pineal research. Oct 2014;57(3):248-61. doi:10.1111/jpi.12164

- Bosch PC. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of certolizumab pegol in women with refractory interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. European urology. 2018;74(5):623-630.

- FDA. Food and Drug Administration. CIMZIA: Highlights of Prescribing Information. Updated 1/2017. Accessed 8/30/2021, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/125160s270lbl.pdf

- Osman NI, Bratt DG, Downey AP, Esperto F, Inman RD, Chapple CR. A Systematic Review of Surgical interventions for the Treatment of Bladder Pain Syndrome/Interstitial Cystitis. European urology focus. Feb 29 2020;doi:10.1016/j.euf.2020.02.014

- Das S. Natural therapeutics for urinary tract infections-a review. Futur J Pharm Sci. 2020;6(1):64. doi:10.1186/s43094-020-00086-2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33215041

- Schoendorfer N, Sharp N, Seipel T, Schauss AG, Ahuja KDK. Urox containing concentrated extracts of Crataeva nurvala stem bark, Equisetum arvense stem and Lindera aggregata root, in the treatment of symptoms of overactive bladder and urinary incontinence: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind placebo controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. Jan 31 2018;18(1):42. doi:10.1186/s12906-018-2101-4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29385990

- Zapala L, Juszczak K, Adamczyk P, et al. New Kid on the Block: The Efficacy of Phytomedicine Extracts Urox((R)) in Reducing Overactive Bladder Symptoms in Rats. Frontiers in molecular biosciences. 2022;9:896624. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2022.896624. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35801157