Dermatitis & Eczema

Dermatitis & Eczema

Last Section Update: 08/2022

Contributor(s): Maureen Williams, ND; Shayna Sandhaus, PhD; Carrie Decker, ND, MS

Table of Contents

- Overview

- Signs & Symptoms of Dermatitis & Eczema

- What Causes Dermatitis & Eczema?

- What Increases the Risk of Dermatitis & Eczema?

- Dermatitis and Eczema: Self-Care for Relief & Prevention

- Diet and Eczema

- Nutrients

- Dermatitis (Eczema): Medical Treatment Options

- Frequently Asked Questions About Dermatitis and Eczema

- Update History

- References

1 Overview

“Dermatitis” means skin inflammation. It is a term used to describe a group of inflammatory skin disorders usually characterized by red, itchy rashes.

The term “eczema” is sometimes used interchangeably with dermatitis. However, eczema usually refers to atopic dermatitis, a common type of dermatitis.1

In this protocol, “eczema” and “atopic dermatitis” are used synonymously.

Eczema affects approximately 13% of children and 5.5% of adults in the US.2-4 It is a chronic and sometimes lifelong condition. Although the vast majority of cases begin in infancy or childhood, the number of adults, including older adults, experiencing new-onset eczema has been increasing.5 In addition to its direct effects on the skin, eczema can take a toll on social and emotional wellbeing.6

Although there is no cure for eczema, it can be managed in part through daily self-care including the use of appropriately formulated moisturizers. Limiting intake of highly processed and fast foods, incorporating fermented and cultured foods, and avoiding foods identified as contributing to symptoms using an elimination diet are strategies that may reduce eczema flare-ups.7-11 In addition, nutrients such as vitamin D, gamma-linolenic acid (GLA), and probiotics have been shown in clinical trials to reduce eczema symptoms.

2 Signs & Symptoms of Dermatitis & Eczema

Dry skin and severe itching are the hallmarks of atopic dermatitis. Eczema often oscillates between periods of exacerbation (flare-ups) and periods in which symptoms lessen. In addition, diagnostic criteria indicate the following may be present12:

- Red bumps (papules) and rash-like patches, which may be dark brown or purple in darker skin tones

- Oozing and crusting along with small fluid-filled blisters (occasionally)

- Scaling and cracking

- Changes in skin pigmentation

- Skin thickening and darkening over time

Young children may be affected on the cheeks and scalp or may have a widely distributed eczematous rash, whereas the backs of the knees and folds of the elbows are more likely to be affected in older children and adults.12

Other forms of dermatitis may cause slightly different symptoms, such as coin-shaped lesions in nummular dermatitis.13

3 What Causes Dermatitis & Eczema?

The common underlying feature of all types of dermatitis is dysfunction of the skin barrier. This is why topical therapies are important in managing symptoms. In a vicious cycle of impairment, the breakdown of healthy skin function can lead to immune system hyperactivation, triggering inflammation and susceptibility to allergies, and disrupt the skin microbiome, resulting in more immune activation, inflammation, and skin barrier dysfunction.14

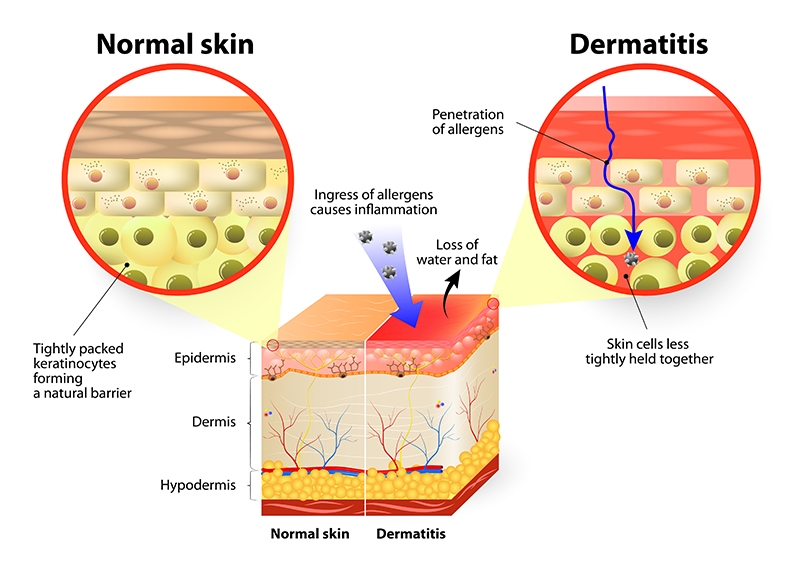

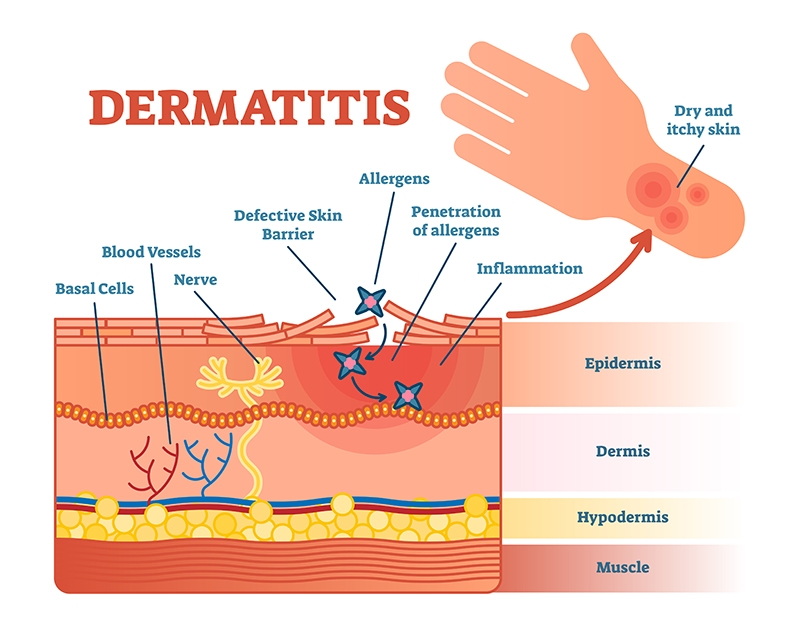

The Anatomy and Function of Skin

Skin is the largest of the body’s organs and consists of three layers: the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis.15 The skin’s barrier function includes acting as the body’s first defense against solar radiation; physical trauma; and toxic, infectious, and allergenic threats in the environment. Critically, skin helps protect against water loss.16,17 The ability of the skin to act as a barrier relies on mechanical, chemical, immunologic, and microbial means.17

Skin Barrier Dysfunction

The stratum corneum, the outermost surface of the epidermis, is made up of specialized cells (corneocytes) that are tightly connected in a strong matrix of proteins (eg, keratin and filaggrin) and lipid compounds (eg, cholesterol, ceramides, and free fatty acids).17 The breakdown of lipids into free fatty acids helps maintain an acidic pH on the skin surface, which inhibits colonization by pathogens.18 Filaggrin is also a source of breakdown products that have antimicrobial action and are part of a group of surface compounds known collectively as natural moisturizing factor.12,19 The stratum corneum regulates skin permeability, controlling water loss and preventing invasion of foreign substances and pathogens. An impaired stratum corneum, typically characterized by increased pH (lower acidity), decreased filaggrin, and changes in ceramide concentrations, is the defining feature of skin barrier dysfunction and a key characteristic of dermatitis.12,19,20 Age-related impaired skin barrier function may play a role in eczema in older individuals.21

Immune Dysfunction

Skin cells (keratinocytes) and immune cells residing in the epidermis are responsible for initiating an immune response to pathogens and other foreign substances. Allergic and other types of skin disease characterized by immune over-activation are important contributing factors in many cases of dermatitis.16 A subgroup of eczema patients have been found to have high serum levels of IgE antibodies, which activate release of histamine. High IgE levels in eczema patients indicate allergic sensitization and are associated with an increased risk of developing food allergies, allergic rhinitis (hay fever), and asthma.16,22,23 In fact, children with eczema have been reported to have a six-fold higher risk of developing a food allergy (IgE-mediated), as well as three-fold higher risk of both allergic rhinitis and asthma later in life.24-27 About 50–75% of children with eczema will develop allergic rhinitis and asthma, a phenomenon known as “atopic march,” and the risk increases with severity of eczema.24 In atopic march, skin barrier dysfunction related to eczema allows allergens to penetrate the body, perpetuating skin inflammation as well as sensitizing the immune system and triggering allergic reactions.24,28 In older adults, age-related changes in immune function, such as immune senescence, may be a contributing factor in the manifestations of atopic dermatitis.5,21 In addition, non-allergic chronic conditions have been found to be more prevalent in elderly individuals with eczema than those without eczema.5

Microbiome Imbalance

The skin microbiome is critical for creating an environment that is inhospitable to pathogens and regulating healthy immune activity in the skin and preventing skin disease. Imbalance in the bacterial and fungal communities (such as yeast, or Candida spp.) living on the skin is a common feature in dermatitis and contributes to barrier dysfunction and immune dysregulation.14,18,29,30 The skin microbiome is influenced by internal conditions (eg, genetics and aging) and external exposures (eg, allergens, hard water, and pollution).21,31 A number of studies have also reported alterations in the gut microbiomes of eczema patients, including infants who later developed eczema, suggesting gut microbial imbalance (dysbiosis) may be a contributing cause of dermatitis. Gut dysbiosis has body-wide effects on immune function that can result in poorly controlled inflammatory responses in diverse tissues, including skin.32,33

4 What Increases the Risk of Dermatitis & Eczema?

Some risk factors for dermatitis cannot be changed. Non-modifiable risk factors include:

- Family history. Family history of allergies, such as eczema, asthma, or allergic rhinitis (hay fever), is the strongest risk factor for eczema.12

- Allergies. Allergies are closely linked to, and appear to exacerbate, eczema.12,16,24

- Female gender. Being female may increase eczema risk.3

- Being very young. This increases risk, since an estimated 70–85% of eczema cases begin by the age of five years.22,34 About 60% of these cases resolve during adolescence.35

Other factors correlated with eczema risk may be modifiable, such as:

- Infant formula feeding. Infants fed formula or solid food in the first few months of life have a higher risk of allergic disease, including eczema, than those fed only breast milk during their first four to six months.36,37

- Antibiotic exposure. Children treated with antibiotics in the first years of life have been found to be more likely to develop eczema, as well as asthma and allergies.38

- Environmental exposure. Urban children are more prone to eczema than their rural counterparts. This may be due to increased pollution in urban settings, and/or the “hygiene hypothesis,” which asserts that early exposure to certain non-pathogenic microbes (eg, through contact with farm animals, pets, siblings, and other children), builds natural immune tolerance.12 Pollution has also been implicated in the rising onset of new eczema in elderly individuals.39

- Obesity. Obesity, especially in childhood, has been correlated with eczema.40

- Living at higher latitudes. Individuals who live at higher latitudes tend to have lower serum vitamin D levels, a factor that has been correlated with increased risk and severity of eczema in some studies.41,42 This also may be due to less exposure to UV light in early infancy.43

- Hard water. Observational studies have found eczema is more common in regions with increased levels of water hardness.31

- Nutrient deficiencies. Deficiencies of essential nutrients, including vitamin A and carotenoids, vitamin D, vitamin B6, zinc, selenium, and essential fatty acids, may contribute to eczema, as well as other skin and allergic conditions.44-46

- Stress. Stress can aggravate all types of dermatitis.47

5 Dermatitis and Eczema: Self-Care for Relief & Prevention

Topicals

Daily use of moisturizers is a cornerstone of therapy for dermatitis and eczema. In fact, most studies show that, for eczema, twice-daily application is indicated.55 Properly formulated moisturizers can help repair skin barrier function, and clinical research shows daily moisturizer use is beneficial in children and adults with eczema. Furthermore, continuous use of moisturizers may help prevent eczema in infants at high risk.55,56

Therapeutic moisturizers should have a similar acidity to skin, with a pH of 4-5, and may contain any of the following55,57:

- Occlusives (protectants), such as lanolin, petrolatum, mineral oil, waxes, dimethicone, and silicone, block water loss through the skin, provide protection against skin irritants, and may reduce inflammation.55,57,58

- Humectants (hydrating agents) like glycerin, hyaluronic acid, urea, and lactate are used to draw moisture from the environment and deeper skin layers.55,57,59

- Emollients (moisturizing agents) provide fatty acids that penetrate the spaces between corneocytes, softening the skin surface.59,60 Plant oils, especially those rich in linoleic acid or gamma-linolenic acid (eg, sea buckthorn oil and borage oil), are emollients sometimes included in therapeutic moisturizers, and may help inhibit inflammation and improve skin barrier function.57

- Therapeutic agents are added to moisturizers for their specific actions. For example, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires all over-the-counter moisturizers claiming to help treat eczema to contain either a low-potency steroid (hydrocortisone) or colloidal oatmeal, a moisturizing skin protectant with anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-itch effects.55 Ceramides are another therapeutic ingredient in some moisturizers, and it has been proposed that combining them with cholesterol and free fatty acids may lead to the greatest benefit.57 Other potentially therapeutic ingredients for topical use include antioxidants and skin probiotics.55,59,61

- Wet wraps. Application of moisturizing and/or therapeutic agents underneath a wet layer of clothing or a bandage may be useful as well. A dry layer of clothing or bandage is placed on top of the damp layer and left over night to sooth flare-ups.62

Daily bathing or showering with warm, but not hot, water for 5–15 minutes promotes skin hydration.69,70 The use of gentle cleansers, only if needed, is recommended. After bathing, patting (rather than rubbing) dry and immediately applying an appropriate moisturizer is recommended.69

Bleach baths, performed using a 0.005% solution of sodium hypochlorite (typically made by adding ¼–½ cup of 6% household bleach to 40 gallons of water),71 have long been recommended for treating eczema.72 Bleach baths have been reported to improve eczema symptoms, decrease inflammation and itching, and restore a healthy skin microbiome by reducing the presence of Staphylococcus aureus, a potential pathogen and frequent colonizer of eczematous skin.73 Laboratory models, however, have been unable to demonstrate antiseptic effects from a 0.005% sodium hypochlorite solution,71 suggesting bleach baths may have more direct anti-inflammatory and anti-itch effects.72 Nevertheless, their benefits appear to be modest: A systematic review and meta-analysis that included data from 10 randomized controlled trials with a total of 307 participants found bleach baths were likely to reduce eczema severity, as reported by a clinician, by roughly 22%, but did not have meaningful and consistent impacts on other outcomes important to eczema patients.74 It is important to note more concentrated solutions are not safe and may worsen skin barrier function and cause serious injury.71

Identifying and avoiding triggers, including allergens and irritants, can be a key practice for some individuals with dermatitis. Common triggers include soaps and detergents, fragrances, wool, temperature and humidity extremes, tight clothing, and stress.69 Frequent hand washing and prolonged use of personal protective gear like medical gloves and face masks can also aggravate eczema and dermatitis; gentle cleansers and frequent use of moisturizers may help those whose work or daily activities require exposure to these kinds of skin irritants.75

6 Diet and Eczema

Food allergies and sensitivities, while unlikely to be the main cause, may be an important contributing factor in atopic dermatitis, particularly in moderate-to-severe cases. Studies indicate as many as 53% of children with eczema have food allergies detectable with skin prick or blood tests, and up to 33% of those with moderate-to-severe eczema show reactions on food challenge tests.69

Cow’s milk, chicken eggs, peanuts, and soybeans are the most common food triggers in younger children, while older children are more likely to react to wheat, tree nuts, fish, and shellfish.69

Food sensitivity (involving IgG antibodies) or allergy (IgE-mediated) testing may be helpful in determining whether certain foods are aggravants in cases of persistent eczema.

An elimination diet in particular has been shown to be a useful tool for identifying trigger foods and generating an individualized dietary plan.7 In addition, high intakes of fast foods, highly processed foods, meat, and energy drinks have been linked to increased eczema risk, while consumption of fermented foods (like kimchi and yogurt) has been correlated with decreased risk.8-11

7 Nutrients

Vitamin D

Adequate vitamin D levels are important to a number of skin conditions, including eczema.76 Meta-analyses of data from observational studies indicate blood vitamin D levels are lower in atopic dermatitis patients than those with healthy skin.41,77 Another systematic review and meta-analysis that included findings from four observational studies noted children born to mothers with lower vitamin D status during pregnancy had a higher risk of developing eczema.78

A placebo-controlled trial with 65 eczema-affected participants used a vitamin D dose of 125 mcg (5,000 IU) per day for 12 weeks, in conjunction with standard therapies, and found those who achieved a blood vitamin D level of 20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L) or higher experienced symptom score improvement.79 Another placebo-controlled trial with 24 subjects found 50 mcg (2,000 IU) vitamin D daily for four weeks not only improved eczema symptom scores but also led to reduced skin colonization by S. aureus, a bacterium associated with skin barrier dysfunction.80 A meta-analysis of data from four randomized placebo-controlled trials found vitamin D supplementation, at doses of 25 mcg (1,000 IU) or 40 mcg (1,600 IU) daily for 1–2 months, effectively reduced eczema symptom severity scores.77 A more recent meta-analysis had similar findings.41

Gamma-linolenic Acid

Gamma-linolenic acid (GLA) is an omega-6 fatty acid with anti-inflammatory effects, and some evidence suggests individuals with atopic dermatitis have a deficiency of the enzyme needed to convert linoleic acid (a common plant-derived omega-6 fatty acid and an essential nutrient) to GLA.81,82 Borage, evening primrose, black currant, and sea buckthorn oils are especially rich in GLA.83 A randomized controlled trial in 50 eczema patients found evening primrose oil, at a dose of 1,800 mg or 3,600 mg (providing 160 mg or 320 mg of GLA, respectively) per day (depending on age), improved eczema symptoms more than the same dose of soybean oil after four months.84 In another controlled trial with 130 adult subjects with dry skin or mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis, a diet enriched with 200 mg GLA per day for 12 weeks improved skin hydration and reduced skin inflammation more than a diet enriched with a soybean/canola oil mixture.85 A trial that included 50 individuals with atopic dermatitis found 500–6,000 mg of evening primrose oil daily, depending on age, for five months was more effective than sunflower oil at reducing eczema symptoms and improving clinical features. Other research in pregnant mothers and infants suggests GLA supplementation may delay the onset and reduce the severity of eczema in childhood.86,87

Plant-derived Ceramides

Skin barrier dysfunction is a key component of dermatitis. Changes in concentrations of ceramides in the skin can contribute to impaired skin barrier function. As a result, ceramides have been increasingly used in topical formulations to protect the integrity of the skin and improve skin hydration.

Ceramides can be formulated into oral preparations as well. These formulas may contain ceramides derived from various plant-based sources such as wheat and konjac. Oral ceramides have been proposed for use in skin conditions such as dermatitis and eczema. Several animal models have shown that oral administration of plant- or bacterial-derived ceramides improved stratum corneum water content, reduced transepidermal water loss, suppressed expression of inflammatory cytokines (eg, interleukin-1 beta [IL-1β] and IL-6), and improved skin flexibility and recovery.162-164

Oral intake of plant-derived ceramides has been shown to improve several aspects of skin health in clinical studies as well. In one clinical study, children with atopic dermatitis were given 1.8 mg daily of konjac-derived ceramides or placebo for two weeks. By the end of the study, skin symptoms and allergic responses improved in the 25 children in the treatment group, but not in the 25 children in the placebo group.165 The same dosage of ceramides was shown to decrease transepidermal water loss in 42 healthy adults after 8-12 weeks compared with placebo.166 And in 14 adult participants aged 20-54 years with mild-to-moderate atopic eczema, 1.8 mg daily of ceramides from konjac decreased transepidermal water loss after 2-8 weeks compared to baseline.167 In a clinical study that enrolled 51 participants randomized to receive placebo or 5 mg per day of ceramides from a konjac extract, intake of ceramides significantly decreased skin dryness, redness, and itching after 3-6 weeks.168 Ceramides derived from wheat have also been shown to improve skin health: a placebo-controlled trial that enrolled 51 women aged 20-63 years with dry skin found that 350 mg of wheat extract oil, rich in ceramides, improved skin hydration after three months of use compared with placebo.169

Probiotics

Numerous clinical trials have shown oral probiotic supplements can reduce both the risk and severity of eczema. Thorough reviews of randomized controlled trials have found certain probiotics, when taken during pregnancy or given during infancy or childhood, can be effective in preventing and treating atopic dermatitis. The best effects have been demonstrated using Lactobacillus species, usually in combination with Bifidobacterium species.88-90 Probiotic strains of L. paracasei, L. rhamnosus, L. acidophilus, L. GG, L. casei, L. salivarius, L. plantarum, B. longum, B. animalis subspecies lactis, and B. bifidum, used in various combinations providing a total of 1 billion colony forming units (CFUs) or more per day, are among those found to have positive effects on atopic dermatitis.88,89

Whey Protein

Whey protein comes from cow’s milk and differs from casein (the main cow’s milk protein) in its make-up, consisting of lactoglobulins, immunoglobulins, bovine albumin, and lactoferrin.91 Small peptides resulting from partial hydrolysis of whey protein are thought to stimulate balanced immune activation leading to enhanced immune tolerance.92 A meta-analysis of findings from eight randomized controlled trials found a partially hydrolyzed whey infant formula, in place of or in addition to breast milk, reduced eczema risk compared with cow’s milk-based formulas in infants with a high risk of allergy and eczema due to family history.93 The results of a review of eight clinical trials further suggests partially hydrolyzed whey-based formula may reduce the risk of atopic dermatitis not just in high-risk infants but in the general infant population, while supporting normal growth and development.94 Animal research suggests partially hydrolyzed whey formula improves skin barrier function,95 which may account in part for its beneficial effects in the context of eczema.

It is important to note that partially hydrolyzed whey-based formulas are not appropriate for infants known to have cow’s milk allergy.96

Vitamin E

Vitamin E is a fat-soluble nutrient that lowers oxidative stress and protects fatty compounds in the body from free radical damage. It has long been known to have an important role in skin health, and low levels have been observed in people with various inflammatory skin problems, including atopic dermatitis.97,98 In a randomized placebo-controlled trial in 70 subjects with atopic dermatitis, 400 IU of vitamin E (form not specified) daily for four months reduced eczema symptoms.99 A placebo-controlled trial with 45 participants found 600 IU of dl-alpha-tocopherol (equivalent to about 300 IU of active d-alpha-tocopherol) per day and 40 mcg (1,600 IU) of vitamin D3 per day each reduced eczema symptoms more than placebo, but treatment with both vitamin E and vitamin D had an even greater positive effect.100 Another trial included 96 subjects with atopic dermatitis and compared treatment with 400 IU of d-alpha-tocopherol daily to placebo. After eight months, great improvement or near complete resolution occurred in 30 (60%) of 50 vitamin E-treated participants but only 1 (2%) of 46 of those given placebo.101

Topical vitamin E is frequently recommended as part of atopic dermatitis treatment.102 A cream containing vitamin E as well as green tea catechin (epigallocatechin gallate, or EGCG) and grape seed procyanidins improved skin symptoms more than a placebo cream in a 28-day clinical trial that included 44 participants with atopic dermatitis affecting the face and/or neck.103 Despite its safety, rare cases of contact dermatitis due to an allergic reaction to topical vitamin E have been reported.104

Melatonin

Sleep disorders are common in those with atopic dermatitis, and while intense itching is an obvious factor, evidence suggests it does not fully explain the relationship.53,54 Poor sleep plays a role in diminished quality of life and triggers a stress response that may even contribute to worsening eczema, thus leading to a vicious cycle.105 Melatonin, a hormone produced in the brain as well as in skin cells, is thought to have a role in dermatitis.106 Melatonin not only regulates circadian rhythms like the sleep and wake cycle, it also reduces skin oxidative stress and inflammation, protects skin against solar radiation damage, and appears to promote wound healing and skin barrier health.53,54,106

An observational study noted lower melatonin levels were associated with greater eczema severity, more intense itch, and poorer sleep in 36 adults with atopic dermatitis.107 A randomized controlled trial investigated the effect of 6 mg of melatonin nightly in 70 children, aged 6–12 years old, with eczema. After six weeks, melatonin-treated children had greater improvement in scores on a symptom severity index and a sleep habit questionnaire compared with those given placebo, although no improvement in itching, time to fall asleep, or total time asleep were recorded. In addition, melatonin decreased levels of IgE, an antibody type linked to atopic dermatitis and other allergic conditions.108 In a crossover trial in 48 children aged 1–18 years old with atopic dermatitis, 3 mg of melatonin nightly for four weeks was more effective than placebo at reducing eczema symptom scores and shortening the time to fall asleep.109

Topical melatonin may have advantages over oral melatonin since it raises skin melatonin concentration while bypassing metabolism in the digestive tract.106 A study using a mouse model of atopic dermatitis indicated topical melatonin may also have beneficial effects.110

Omega-3 fatty acids

Omega-3 fatty acids, like eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) from fish oil, have well-known anti-inflammatory effects. Some research suggests higher intake of these fatty acids during pregnancy and nursing is associated with lower risk of infant and childhood eczema and other allergic conditions, but not all studies agree.111,112 Likewise, most, but not all, studies have noted a correlation between higher fish intake during infancy and childhood and lower incidence of allergic diseases including atopic dermatitis.113 In a controlled trial that included 53 adults with atopic dermatitis, eight weeks of treatment with 5.4 grams of DHA daily resulted in reductions in eczema symptoms scores compared with a saturated fat placebo.114 A trial that included 31 atopic dermatitis patients given either 10 grams (about 2 teaspoons) of fish oil, providing 1.8 grams of EPA, daily or a placebo containing olive oil found fish oil-treated subjects had greater reductions in scaling, itching, and overall severity after 12 weeks.115 In another trial in 22 patients with moderate-to-severe eczema, 10 days of daily intravenous (IV) treatments with 200 mL of a 10% fish oil emulsion or a 10% soybean oil (high in the omega-6 fatty acid, linolenic acid) emulsion led to improvements in eczema symptoms, but the benefits were greater in those treated with IV fish oil.116

Zinc

Zinc is needed for normal skin function and repair, and zinc deficiency has been reported to be more common in those with atopic dermatitis.117 However, few clinical trials have examined the use of zinc to treat eczema. A controlled trial in 58 children with eczema, aged 2–14 years, whose hair zinc levels were low found 12 mg of zinc (as zinc oxide) daily for eight weeks reduced itching and improved skin hydration.118 However, zinc sulfate, at a dose of 185.4 mg (equivalent to about 43 mg of elemental zinc) daily, did not improve symptom severity in an eight-week placebo-controlled trial in 50 children aged 1–16 years with atopic dermatitis and unknown zinc status,119 suggesting appropriate dosing and patient selection may be key to getting good results.

Topical zinc may also have a role in managing atopic dermatitis. In an uncontrolled clinical trial, a zinc oxide cream that contained anti-inflammatory herbal extracts and starch was used to treat 30 children with mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis affecting the face, arms, or trunk. After six weeks, 87% of the children had >50% improvement in eczema symptom severity scores.120 One interesting study found that sleeping in garments made with a zinc oxide-impregnated material for three consecutive nights reduced symptom severity and itching and led to improved sleep in individuals with atopic dermatitis.121

Honey

Honey is a complex substance made mostly of fructose and glucose, but is also rich in flavonoids, organic acids, and other phytochemicals, some of which have potent anti-inflammatory, oxidative stress-reducing, and antimicrobial capacities.122 In an uncontrolled pilot trial, 16 atopic dermatitis patients with two or more similar lesions were given pure manuka honey to apply to some of their lesions every night for seven consecutive nights, covering it with gauze and washing it off in the morning. Two patients experienced worsening of their skin symptoms within two nights and discontinued honey treatment; however, in the remaining 14 participants, treated lesions improved while untreated ones did not. In addition, three (21%) of the 14 reported sustained improvement one year later.123 One study found a topical compound made of equal parts honey, beeswax, and olive oil substantially improved symptoms in eight (80%) of 10 untreated atopic dermatitis patients. In the same study, 11 atopic dermatitis patients who were being treated with topical corticosteroids replaced this treatment with a corticosteroid plus honey/beeswax/olive oil mixture, using varying ratios. Five (45%) of the 11 had no worsening of symptoms even after using a formula providing 75% less corticosteroid than they had been using at the beginning of the study.124

Curcumin

Curcumin, a yellow pigment flavonoid from turmeric, has well-known anti-inflammatory effects. Preclinical evidence indicates both oral and topical curcumin may have a role in treating skin disorders, including atopic and contact (or irritant) dermatitis.125,126 In an open clinical trial that included 42 atopic dermatitis patients receiving standard topical care, those who also took 500 mg of curcumin phytosome (a bioavailable form of curcumin) twice daily had better skin hydration and elasticity and lower symptom severity compared with those who used standard measures alone.127 A cream made with extracts of six medicinal herbs, including turmeric, was reported to decrease eczema symptoms after four weeks in 150 atopic dermatitis patients.128 In a placebo-controlled trial with 96 participants, 1 gram of curcumin daily for four weeks reduced itching and increased quality of life in men with chronic dermatitis due to toxic mustard exposure.129 Studies in mice suggest curcumin can suppress the inflammatory response involved in atopic dermatitis and lower the risk of progressive allergic disease.130,131

Quercetin

Quercetin is one of the most abundant flavonoids in the diet and has been shown to inhibit inflammatory signaling and reduce histamine release. Numerous laboratory and animal studies indicate quercetin has the potential to help in treating atopic dermatitis.132,133 In 10 nickel-allergic volunteers, taking 2 grams per day of quercetin for three days reduced their nickel reactions: eight subjects had 50% reductions and two had 100% reductions in their reactions.134 In addition, 1 gram of quercetin, taken two hours before light exposure, was reported to reduce photosensitivity dermatitis (an eczema-like reaction to light [usually sunlight] exposure) in a study with nine subjects.134

Vitamin C

Vitamin C is a water-soluble free radical scavenger that is highly concentrated in the skin’s outermost layer.135 Vitamin C has an important role in maintaining the skin barrier, and some evidence suggests it has anti-histamine and anti-allergy effects.135-137 Skin affected by atopic dermatitis has been found to have lower vitamin C concentrations than healthy skin.138 A study in 17 adults with atopic dermatitis found decreasing blood vitamin C levels were associated with decreasing skin ceramide (a protective lipid) levels and increasing severity of eczema symptoms.139 A study that included 65 women with a history of allergies found a diet richer in vitamin C increased vitamin C levels in breast milk and was associated with lower incidence of atopic dermatitis in their offspring during their first year of life; however, supplemental vitamin C had no effect on breast milk levels or risk of atopic dermatitis in the infants.140 Although vitamin C is not easily absorbed into the skin, a topical cream containing vitamin C in a zinc oxide base was found to reduce skin inflammation in a mouse model of atopic dermatitis.141

Vitamin A and Carotenoids

Vitamin A is a fat-soluble essential nutrient needed for immune function and healthy mucosal (eg, lining of the gut and respiratory system) and epithelial (eg, skin) barrier function. Vitamin A deficiency is associated with skin inflammation, poor wound healing, disruption of the skin microbiome, and increased skin infection risk.142 Carotenes are precursors to vitamin A and, along with related compounds called carotenoids, have unique immune-modulating and antioxidant effects. Observational evidence indicates individuals with atopic dermatitis have abnormal vitamin A metabolism, lower skin and blood levels of vitamin A, and lower blood levels of the carotenoids lutein and zeaxanthin.46,143 Studies in animal models of atopic dermatitis indicate beta-carotene and the carotenoid astaxanthin may have anti-eczema effects.144,145

Sea Buckthorn

Sea buckthorn oil is rich in flavonoids, carotenoids, polyunsaturated fatty acids (like GLA), and other phytochemicals, and has been used historically to treat dermatitis and other skin disorders. Preclinical evidence shows it may possess antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and wound-healing effects.146 One laboratory study indicated sea buckthorn oil may reverse the negative effects of S. aureus on skin cell function,147 and several animal studies suggest it can reduce eczema.148,149 A clinical trial in 49 atopic dermatitis patients found 5 grams of oil derived from sea buckthorn’s fruit pulp, taken daily for four months, led to significant symptom improvement.150

8 Dermatitis (Eczema): Medical Treatment Options

In cases of atopic dermatitis that does not improve sufficiently with self-care and nutritional approaches, a health care provider may suggest topical anti-inflammatory agents, such as topical corticosteroids or the calcineurin inhibitors tacrolimus (Protopic) or pimecrolimus (Elidel), as the first line of therapy.5,151,152 It is important to note that long-term use of topical corticosteroids can have a number of negative effects, including damaging skin structure, causing rebound inflammation and dilation of superficial capillaries, interfering with skin repair, and increasing susceptibility to skin infections.153 Therefore, people with eczema should discuss the use of these topical medications with a qualified health care provider.

Newer topical medications for atopic dermatitis include crisaborole (Eucrisa, a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor) and ruxolitinib (Opzelura, a Janus kinase inhibitor), both of which suppress inflammation.151

Oral antihistamines are sometimes helpful in conjunction with these therapies, especially for reducing itch, and oral antimicrobials may be useful in cases with apparent infection.5,152,154 Oral antihistamines like diphenhydramine (Benadryl) or cetirizine (Zyrtec) are sometimes prescribed for itching due to eczema; however, many eczema patients experience intractable itch that does not respond fully to antihistamine therapy.151,155 Emerging preclinical and clinical evidence suggests agents that inhibit H4 histamine receptors (as opposed to the H1 histamine receptors targeted by traditional anti-allergy medications) may have a role in treating skin disorders characterized by itch.156 Generally, sedating (first-generation) antihistamines are preferable for night time use, and non-sedating (second-generation) antihistamines are better suited for daytime use.

Light therapy using narrow-band ultraviolet B light has been found to benefit those with chronic, moderate-to-severe, atopic dermatitis.154

Oral immunosuppressive drugs are sometimes recommended in moderate-to-severe cases or flare-ups, but all these medications can cause serious adverse side effects and are best used short-term. They include oral corticosteroids like prednisone (Deltasone), or alternatives such as cyclosporine (also spelled ciclosporin) (Sandimmune), dupilumab (Dupixent), methotrexate (Rheumatrex), or azathioprine (Imuran).154

Allergen-specific immunotherapy may be useful as well. Immunotherapy involves regular, repeated exposure to low doses of the allergen thought to contribute to symptoms. Over time, the repeated low-dose exposures may help “train” the immune system to tolerate the trigger rather than react to it with inflammation. Immunotherapy is generally delivered under the skin (subcutaneous) or under the tongue (sublingual).157

9 Frequently Asked Questions About Dermatitis and Eczema

What is atopic dermatitis?

Atopic dermatitis, which is also called eczema, is a common red, itchy skin condition related to allergies.1

How is atopic dermatitis treated?

Daily use of therapeutic moisturizers is the cornerstone of eczema treatment. Steroid creams and other anti-inflammatory treatments are widely used during flare-ups.151

What causes atopic dermatitis?

The cause is multifaceted, and may include immune over-reactivity (like allergy), changes in the gut and skin microbiomes, pollutants in the environment, and other factors.12,14,32

Is atopic dermatitis contagious?

No, you cannot get atopic dermatitis from someone with this condition.

Is atopic dermatitis the same as eczema?

Typically, the term eczema is used to mean atopic dermatitis, but sometimes it is used more broadly to describe any type of skin inflammation.1

What does eczema look like?

Usually, eczema appears as pink, red, dark brown, or purple patches, and red bumps. More severe eczema may have scaling, cracking, oozing, and crusting. Over time, skin with eczema becomes thickened due to chronic scratching.12

Can you treat eczema without steroids?

Yes, many people manage mild eczema with careful bathing and moisturizing habits; avoiding allergenic foods; reducing stress; taking targeted supplements; and occasionally using over-the-counter, steroid-free, topical medications.151

How do you treat eczema on the scalp?

Seborrheic dermatitis (commonly referred to as dandruff) is very similar in appearance to eczema, but it is local to regions with hair, like the scalp. This condition is commonly treated with a medicated shampoo, however, topical steroids may be prescribed.151

How do you treat eczema around the eyes?

Eczema around the eyes may lead to serious complications, including those that may impact vision, and should be treated by an eye specialist, known as an ophthalmologist.158

What nutrients may be good for eczema?

Vitamin D,159 gamma-linolenic acid,160 probiotics,90 whey protein,161 and vitamin E104 are some nutrients that may help with eczema.

How is eczema diagnosed?

Several diagnostic criteria have been developed to help facilitate eczema diagnosis and epidemiologic study. The diagnosis is generally made clinically by an experienced health care provider.

Disclaimer and Safety Information

This information (and any accompanying material) is not intended to replace the attention or advice of a physician or other qualified health care professional. Anyone who wishes to embark on any dietary, drug, exercise, or other lifestyle change intended to prevent or treat a specific disease or condition should first consult with and seek clearance from a physician or other qualified health care professional. Pregnant women in particular should seek the advice of a physician before using any protocol listed on this website. The protocols described on this website are for adults only, unless otherwise specified. Product labels may contain important safety information and the most recent product information provided by the product manufacturers should be carefully reviewed prior to use to verify the dose, administration, and contraindications. National, state, and local laws may vary regarding the use and application of many of the therapies discussed. The reader assumes the risk of any injuries. The authors and publishers, their affiliates and assigns are not liable for any injury and/or damage to persons arising from this protocol and expressly disclaim responsibility for any adverse effects resulting from the use of the information contained herein.

The protocols raise many issues that are subject to change as new data emerge. None of our suggested protocol regimens can guarantee health benefits. Life Extension has not performed independent verification of the data contained in the referenced materials, and expressly disclaims responsibility for any error in the literature.

- Weston WL, Howe W. Overview of dermatitis (eczema). UpToDate. Accessed Feb. 25, 2022, https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-dermatitis-eczema

- Silverberg JI. Public Health Burden and Epidemiology of Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatologic clinics. Jul 2017;35(3):283-289. doi:10.1016/j.det.2017.02.002. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28577797

- Leasure AC, Cohen JM. Prevalence of eczema among adults in the United States: a cross-sectional study in the All of Us research program. Archives of dermatological research. Feb 11 2022;doi:10.1007/s00403-022-02328-0. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35147780

- Hou A, Silverberg JI. Secular trends of atopic dermatitis and its comorbidities in United States children between 1997 and 2018. Archives of dermatological research. Apr 2022;314(3):267-274. doi:10.1007/s00403-021-02219-w. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00403-021-02219-w

- Tanei R. Atopic Dermatitis in Older Adults: A Review of Treatment Options. Drugs Aging. Mar 2020;37(3):149-160. doi:10.1007/s40266-020-00750-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32086792

- Koszoru K, Borza J, Gulacsi L, Sardy M. Quality of life in patients with atopic dermatitis. Cutis. Sep 2019;104(3):174-177. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31675393

- Das A, Panda S. Role of elimination diet in atopic dermatitis: current evidence and understanding. Indian Journal of Paediatric Dermatology. 2021;22(1):21.

- Park S, Choi HS, Bae JH. Instant noodles, processed food intake, and dietary pattern are associated with atopic dermatitis in an adult population (KNHANES 2009-2011). Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2016;25(3):602-13. doi:10.6133/apjcn.092015.23.

- Shoda T, Futamura M, Yang L, Narita M, Saito H, Ohya Y. Yogurt consumption in infancy is inversely associated with atopic dermatitis and food sensitization at 5 years of age: A hospital-based birth cohort study. J Dermatol Sci. May 2017;86(2):90-96. doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2017.01.006. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28108060

- Park S, Bae JH. Fermented food intake is associated with a reduced likelihood of atopic dermatitis in an adult population (Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2012-2013). Nutr Res. Feb 2016;36(2):125-33. doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2015.11.011.

- Cho SI, Lee H, Lee DH, Kim KH. Association of frequent intake of fast foods, energy drinks, or convenience food with atopic dermatitis in adolescents. European journal of nutrition. Oct 2020;59(7):3171-3182. doi:10.1007/s00394-019-02157-4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31822988

- Weston WL, Howe W. Atopic dermatitis (eczema): Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis. Accessed Feb. 25, 2022, https://www.uptodate.com/contents/atopic-dermatitis-eczema-pathogenesis-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis

- Robinson CA, Love LW, Farci F. Nummular Dermatitis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2022, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2022.

- Blicharz L, Rudnicka L, Czuwara J, et al. The Influence of Microbiome Dysbiosis and Bacterial Biofilms on Epidermal Barrier Function in Atopic Dermatitis-An Update. International journal of molecular sciences. Aug 5 2021;22(16)doi:10.3390/ijms22168403. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34445108

- Cleveland Clinic. Skin. Updated 10/13/2021. Accessed 5/26/2022, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/10978-skin

- Farinazzo E, Giuffrida R, Dianzani C, et al. What makes an inflammatory disease inflammatory? An overview of inflammatory mechanisms of allergic contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. Dec 2020;155(6):719-723. doi:10.23736/S0392-0488.20.06551-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32348082

- Pelc J, Czarnecka-Operacz M, Adamski Z. Structure and function of the epidermal barrier in patients with atopic dermatitis - treatment options. Part one. Postepy dermatologii i alergologii. Feb 2018;35(1):1-5. doi:10.5114/ada.2018.73159. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29599666

- Swaney MH, Kalan LR. Living in Your Skin: Microbes, Molecules, and Mechanisms. Infect Immun. Mar 17 2021;89(4)doi:10.1128/iai.00695-20.

- Pavel P, Blunder S, Moosbrugger-Martinz V, Elias PM, Dubrac S. Atopic Dermatitis: The Fate of the Fat. International journal of molecular sciences. Feb 14 2022;23(4)doi:10.3390/ijms23042121. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35216234

- Fujii M. The Pathogenic and Therapeutic Implications of Ceramide Abnormalities in Atopic Dermatitis. Cells. Sep 10 2021;10(9)doi:10.3390/cells10092386. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34572035

- Bocheva GS, Slominski RM, Slominski AT. Immunological Aspects of Skin Aging in Atopic Dermatitis. Int J Mol Sci. May 27 2021;22(11)doi:10.3390/ijms22115729. https://mdpi-res.com/d_attachment/ijms/ijms-22-05729/article_deploy/ijms-22-05729.pdf?version=1622116346

- Mocanu M, Vâță D, Alexa AI, et al. Atopic Dermatitis-Beyond the Skin. Diagnostics (Basel). Aug 27 2021;11(9)doi:10.3390/diagnostics11091553. https://mdpi-res.com/d_attachment/diagnostics/diagnostics-11-01553/article_deploy/diagnostics-11-01553.pdf?version=1630056305

- Tanaka S, Furuta K. Roles of IgE and Histamine in Mast Cell Maturation. Cells. Aug 23 2021;10(8)doi:10.3390/cells10082170. https://mdpi-res.com/d_attachment/cells/cells-10-02170/article_deploy/cells-10-02170-v2.pdf?version=1629796841

- Tsuge M, Ikeda M, Matsumoto N, Yorifuji T, Tsukahara H. Current Insights into Atopic March. Children (Basel). Nov 19 2021;8(11)doi:10.3390/children8111067. https://mdpi-res.com/d_attachment/children/children-08-01067/article_deploy/children-08-01067.pdf?version=1637311395

- Knudgaard MH, Andreasen TH, Ravnborg N, et al. Rhinitis prevalence and association with atopic dermatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. Jul 2021;127(1):49-56.e1. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2021.02.026. https://www.annallergy.org/article/S1081-1206(21)00172-1/fulltext

- Ravnborg N, Ambikaibalan D, Agnihotri G, et al. Prevalence of asthma in patients with atopic dermatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. Feb 2021;84(2):471-478. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.055. https://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(20)30299-1/fulltext

- Yang L, Fu J, Zhou Y. Research Progress in Atopic March. Review. Front Immunol. 2020-August-27 2020;11:1907. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.01907. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32973790

- Suaini NHA, Siah KTH, Tham EH. Role of the gut-skin axis in IgE-mediated food allergy and atopic diseases. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. Nov 1 2021;37(6):557-564. doi:10.1097/mog.0000000000000780. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/wk/cogas/2021/00000037/00000006/art00004

- Tao R, Li R, Wang R. Dysbiosis of skin mycobiome in atopic dermatitis. Mycoses. Mar 2022;65(3):285-293. doi:10.1111/myc.13402. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34817898

- Nowicka D, Chilicka K, Dziendziora-Urbinska I. Host-Microbe Interaction on the Skin and Its Role in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis. Pathogens. Jan 6 2022;11(1)doi:10.3390/pathogens11010071. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35056019

- Stefanovic N, Irvine AD, Flohr C. The Role of the Environment and Exposome in Atopic Dermatitis. Curr Treat Options Allergy. 2021;8(3):222-241. doi:10.1007/s40521-021-00289-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8139547/pdf/40521_2021_Article_289.pdf

- Fang Z, Li L, Zhang H, Zhao J, Lu W, Chen W. Gut Microbiota, Probiotics, and Their Interactions in Prevention and Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis: A Review. Front Immunol. 2021;12:720393. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.720393. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8317022/pdf/fimmu-12-720393.pdf

- Park DH, Kim JW, Park HJ, Hahm DH. Comparative Analysis of the Microbiome across the Gut-Skin Axis in Atopic Dermatitis. Int J Mol Sci. Apr 19 2021;22(8)doi:10.3390/ijms22084228. https://mdpi-res.com/d_attachment/ijms/ijms-22-04228/article_deploy/ijms-22-04228-v2.pdf?version=1618912446

- Yang L, Fu J, Zhou Y. Research Progress in Atopic March. Review. Frontiers in Immunology. 2020-August-27 2020;11doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.01907. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01907

- Raimondo A, Lembo S. Atopic Dermatitis: Epidemiology and Clinical Phenotypes. Dermatology practical & conceptual. Oct 2021;11(4):e2021146. doi:10.5826/dpc.1104a146. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35024238

- Nuzzi G, Di Cicco ME, Peroni DG. Breastfeeding and Allergic Diseases: What's New? Children (Basel). Apr 24 2021;8(5)doi:10.3390/children8050330. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33923294

- Garcia-Ricobaraza M, Garcia-Santos JA, Escudero-Marin M, Dieguez E, Cerdo T, Campoy C. Short- and Long-Term Implications of Human Milk Microbiota on Maternal and Child Health. International journal of molecular sciences. Nov 1 2021;22(21)doi:10.3390/ijms222111866. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34769296

- Duong QA, Pittet LF, Curtis N, Zimmermann P. Antibiotic exposure and adverse long-term health outcomes in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of infection. Jan 9 2022;doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2022.01.005. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35021114

- Tétart F, Joly P. Eczema in elderly people. Eur J Dermatol. Dec 1 2020;30(6):663-667. doi:10.1684/ejd.2020.3915. http://www.jle.com/fr/revues/ejd/e-docs/eczema_in_elderly_people_319016/article.phtml

- Jimenez-Cortegana C, Ortiz-Garcia G, Serrano A, Moreno-Ramirez D, Sanchez-Margalet V. Possible Role of Leptin in Atopic Dermatitis: A Literature Review. Biomolecules. Nov 5 2021;11(11)doi:10.3390/biom11111642. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34827640

- Ng JC, Yew YW. Effect of Vitamin D Serum Levels and Supplementation on Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. American journal of clinical dermatology. Mar 5 2022;doi:10.1007/s40257-022-00677-0. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35246808

- Palmer DJ. Vitamin D and the Development of Atopic Eczema. J Clin Med. May 20 2015;4(5):1036-50. doi:10.3390/jcm4051036. https://mdpi-res.com/d_attachment/jcm/jcm-04-01036/article_deploy/jcm-04-01036.pdf?version=1432107909

- Rueter K, Jones AP, Siafarikas A, et al. Direct infant UV light exposure is associated with eczema and immune development. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. Mar 2019;143(3):1012-1020.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2018.08.037.

- Vaughn AR, Foolad N, Maarouf M, Tran KA, Shi VY. Micronutrients in Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, NY). Jun 2019;25(6):567-577. doi:10.1089/acm.2018.0363. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30912673

- Balic A, Vlasic D, Zuzul K, Marinovic B, Bukvic Mokos Z. Omega-3 Versus Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in the Prevention and Treatment of Inflammatory Skin Diseases. International journal of molecular sciences. Jan 23 2020;21(3):741. doi:10.3390/ijms21030741. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31979308

- Lucas R, Mihaly J, Lowe GM, et al. Reduced Carotenoid and Retinoid Concentrations and Altered Lycopene Isomer Ratio in Plasma of Atopic Dermatitis Patients. Nutrients. Oct 1 2018;10(10)doi:10.3390/nu10101390. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30275368

- Clark GW, Pope SM, Jaboori KA. Diagnosis and treatment of seborrheic dermatitis. American family physician. Feb 01 2015;91(3):185-90.

- Bawany F, Northcott CA, Beck LA, Pigeon WR. Sleep Disturbances and Atopic Dermatitis: Relationships, Methods for Assessment, and Therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. Apr 2021;9(4):1488-1500. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2020.12.007. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9026738/pdf/nihms-1796191.pdf

- Podder I, Mondal H, Kroumpouzos G. Nocturnal pruritus and sleep disturbance associated with dermatologic disorders in adult patients. Int J Womens Dermatol. Sep 2021;7(4):403-410. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.02.010. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8484989/pdf/main.pdf

- Ghani H, Jamgochian M, Pappert A, Rahman R, Cubeli S. The Psychosocial Burden Associated With and Effective Treatment Approach for Atopic Dermatitis: A Literature Review. J Drugs Dermatol. Oct 1 2021;20(10):1046-1050. doi:10.36849/jdd.6328.

- Sanders KM, Akiyama T. The vicious cycle of itch and anxiety. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. Apr 2018;87:17-26. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.01.009. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5845794/pdf/nihms939480.pdf

- Sawada Y, Saito-Sasaki N, Mashima E, Nakamura M. Daily Lifestyle and Inflammatory Skin Diseases. International journal of molecular sciences. May 14 2021;22(10)doi:10.3390/ijms22105204. https://mdpi-res.com/d_attachment/ijms/ijms-22-05204/article_deploy/ijms-22-05204.pdf?version=1620990809

- Jaworek AK, Szepietowski JC, Halubiec P, Wojas-Pelc A, Jaworek J. Melatonin as an Antioxidant and Immunomodulator in Atopic Dermatitis-A New Look on an Old Story: A Review. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland). Jul 24 2021;10(8)doi:10.3390/antiox10081179. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34439427

- Chang YS, Chiang BL. Mechanism of Sleep Disturbance in Children with Atopic Dermatitis and the Role of the Circadian Rhythm and Melatonin. International journal of molecular sciences. Mar 29 2016;17(4):462. doi:10.3390/ijms17040462. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27043528

- Hebert AA, Rippke F, Weber TM, Nicol NH. Efficacy of Nonprescription Moisturizers for Atopic Dermatitis: An Updated Review of Clinical Evidence. American journal of clinical dermatology. Oct 2020;21(5):641-655. doi:10.1007/s40257-020-00529-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32524381

- Zhong Y, Samuel M, van Bever H, Tham EH. Emollients in infancy to prevent atopic dermatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. Sep 30 2021;doi:10.1111/all.15116. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34591995

- Elias PM. Optimizing Emollient Therapy for Skin Barrier Repair in Atopic Dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. Jan 19 2022;doi:10.1016/j.anai.2022.01.012. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35065300 https://www.annallergy.org/article/S1081-1206(22)00015-1/pdf

- Purnamawati S, Indrastuti N, Danarti R, Saefudin T. The Role of Moisturizers in Addressing Various Kinds of Dermatitis: A Review. Clin Med Res. Dec 2017;15(3-4):75-87. doi:10.3121/cmr.2017.1363. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29229630

- Chandan N, Rajkumar JR, Shi VY, Lio PA. A new era of moisturizers. Journal of cosmetic dermatology. Aug 2021;20(8):2425-2430. doi:10.1111/jocd.14217. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33977643

- National Eczema Society. Emollients. Accessed 5/26/2022, https://eczema.org/information-and-advice/treatments-for-eczema/emollients/

- Franca K. Topical Probiotics in Dermatological Therapy and Skincare: A Concise Review. Dermatology and therapy. Feb 2021;11(1):71-77. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00476-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33340341

- Spergel JM, Lio PA, Dellavalle RP, et al. Management of severe atopic dermatitis (eczema) in children. UpToDate. Updated Aug. 9, 2021. Accessed Jun. 28, 2022, https://www.uptodate.com/contents/management-of-severe-atopic-dermatitis-eczema-in-children?search=wet-wrap&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~8&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

- Xu S, Kwa M, Lohman ME, Evers-Meltzer R, Silverberg JI. Consumer Preferences, Product Characteristics, and Potentially Allergenic Ingredients in Best-selling Moisturizers. JAMA Dermatol. Nov 1 2017;153(11):1099-1105. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.3046. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamadermatology/articlepdf/2652353/jamadermatology_xu_2017_oi_170041.pdf

- Cohen SR, Cárdenas-de la Garza JA, Dekker P, et al. Allergic Contact Dermatitis Secondary to Moisturizers. J Cutan Med Surg. Jul/Aug 2020;24(4):350-359. doi:10.1177/1203475420919396.

- DeKoven JG, Silverberg JI, Warshaw EM, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group Patch Test Results: 2017-2018. Dermatitis. Mar-Apr 01 2021;32(2):111-123. doi:10.1097/der.0000000000000729.

- Schlichte MJ, Katta R. Methylisothiazolinone: an emergent allergen in common pediatric skin care products. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:132564. doi:10.1155/2014/132564. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4197884/pdf/DRP2014-132564.pdf

- NEA. Naitonal Eczema Association. 8 Skincare Ingredients to Avoid If ou Have Eczema, According to Dermatologists. Available at https://nationaleczema.org/8-skincare-ingredients-to-avoid/ Last updated 10/30/2020. Accessed 04/30/2022. 2020;

- Bhanot A, Huntley A, Ridd MJ. Adverse Events from Emollient Use in Eczema: A Restricted Review of Published Data. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). Jun 2019;9(2):193-208. doi:10.1007/s13555-019-0284-3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6522630/pdf/13555_2019_Article_284.pdf

- Narla S, Silverberg JI. Dermatology for the internist: optimal diagnosis and management of atopic dermatitis. Ann Med. Dec 2021;53(1):2165-2177. doi:10.1080/07853890.2021.2004322. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34787024 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8604464/pdf/IANN_53_2004322.pdf

- Johnson BB, Franco AI, Beck LA, Prezzano JC. Treatment-resistant atopic dermatitis: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:181-192. doi:10.2147/CCID.S163814. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30962700https://www.dovepress.com/getfile.php?fileID=48649

- Sawada Y, Tong Y, Barangi M, et al. Dilute bleach baths used for treatment of atopic dermatitis are not antimicrobial in vitro. J Allergy Clin Immunol. May 2019;143(5):1946-1948. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2019.01.009. https://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(19)30069-7/pdf

- Krynicka K, Trzeciak M. The role of sodium hypochlorite in atopic dermatitis therapy: a narrative review. Int J Dermatol. Feb 15 2022;doi:10.1111/ijd.16099.

- Maarouf M, Shi VY. Bleach for Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatitis. May/Jun 2018;29(3):120-126. doi:10.1097/der.0000000000000358.

- Bakaa L, Pernica JM, Couban RJ, et al. Bleach baths for atopic dermatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis including unpublished data, Bayesian interpretation, and GRADE. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. Mar 30 2022;doi:10.1016/j.anai.2022.03.024.

- Mandlik DS, Mandlik SK. Atopic dermatitis: new insight into the etiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and novel treatment strategies. Immunopharmacology and immunotoxicology. Apr 2021;43(2):105-125. doi:10.1080/08923973.2021.1889583. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33645388

- Kechichian E, Ezzedine K. Vitamin D and the Skin: An Update for Dermatologists. American journal of clinical dermatology. Apr 2018;19(2):223-235. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0323-8.

- Kim MJ, Kim SN, Lee YW, Choe YB, Ahn KJ. Vitamin D Status and Efficacy of Vitamin D Supplementation in Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. Dec 3 2016;8(12)doi:10.3390/nu8120789. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27918470

- Wei Z, Zhang J, Yu X. Maternal vitamin D status and childhood asthma, wheeze, and eczema: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. Sep 2016;27(6):612-9. doi:10.1111/pai.12593. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27145360

- Sanchez-Armendariz K, Garcia-Gil A, Romero CA, et al. Oral vitamin D3 5000 IU/day as an adjuvant in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: a randomized control trial. Int J Dermatol. Dec 2018;57(12):1516-1520. doi:10.1111/ijd.14220. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30238557

- Udompataikul M, Huajai S, Chalermchai T, Taweechotipatr M, Kamanamool N. The Effects of Oral Vitamin D Supplement on Atopic Dermatitis: A Clinical Trial with Staphylococcus aureus Colonization Determination. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand = Chotmaihet thangphaet . Oct 2015;98 Suppl 9:S23-30. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26817206

- Horrobin DF. Fatty acid metabolism in health and disease: the role of delta-6-desaturase. Am J Clin Nutr. May 1993;57(5 Suppl):732S-736S; discussion 736S-737S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/57.5.732S. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8386433

- Yen CH, Dai YS, Yang YH, Wang LC, Lee JH, Chiang BL. Linoleic acid metabolite levels and transepidermal water loss in children with atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. Jan 2008;100(1):66-73. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60407-3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18254485

- Zielińska A, Nowak I. Abundance of active ingredients in sea-buckthorn oil. Lipids in health and disease. May 19 2017;16(1):95. doi:10.1186/s12944-017-0469-7.

- Chung BY, Park SY, Jung MJ, Kim HO, Park CW. Effect of Evening Primrose Oil on Korean Patients With Mild Atopic Dermatitis: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Study. Annals of dermatology. Aug 2018;30(4):409-416. doi:10.5021/ad.2018.30.4.409. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30065580

- Senapati S, Banerjee S, Gangopadhyay DN. Evening primrose oil is effective in atopic dermatitis: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. Sep-Oct 2008;74(5):447-52. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.42645. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19052401

- van Gool CJ, Thijs C, Henquet CJ, et al. Gamma-linolenic acid supplementation for prophylaxis of atopic dermatitis--a randomized controlled trial in infants at high familial risk. Am J Clin Nutr. Apr 2003;77(4):943-51. doi:10.1093/ajcn/77.4.943. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12663296

- Linnamaa P, Savolainen J, Koulu L, et al. Blackcurrant seed oil for prevention of atopic dermatitis in newborns: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Exp Allergy. Aug 2010;40(8):1247-55. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03540.x. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20545710

- Tan-Lim CSC, Esteban-Ipac NAR, Recto MST, Castor MAR, Casis-Hao RJ, Nano ALM. Comparative effectiveness of probiotic strains on the prevention of pediatric atopic dermatitis: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. Aug 2021;32(6):1255-1270. doi:10.1111/pai.13514. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33811784

- Jiang W, Ni B, Liu Z, et al. The Role of Probiotics in the Prevention and Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis in Children: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Paediatr Drugs. Oct 2020;22(5):535-549. doi:10.1007/s40272-020-00410-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32748341

- Amalia N, Orchard D, Francis KL, King E. Systematic review and meta-analysis on the use of probiotic supplementation in pregnant mother, breastfeeding mother and infant for the prevention of atopic dermatitis in children. The Australasian journal of dermatology. May 2020;61(2):e158-e173. doi:10.1111/ajd.13186. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31721162

- Cabana MD. The Role of Hydrolyzed Formula in Allergy Prevention. Ann Nutr Metab. 2017;70 Suppl 2:38-45. doi:10.1159/000460269. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28521324

- Vandenplas Y, Munasir Z, Hegar B, et al. A perspective on partially hydrolyzed protein infant formula in nonexclusively breastfed infants. Korean journal of pediatrics. May 2019;62(5):149-154. doi:10.3345/kjp.2018.07276. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30651423

- Szajewska H, Horvath A. A partially hydrolyzed 100% whey formula and the risk of eczema and any allergy: an updated meta-analysis. The World Allergy Organization journal. 2017;10(1):27. doi:10.1186/s40413-017-0158-z. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28781718

- Sauser J, Nutten S, de Groot N, et al. Partially Hydrolyzed Whey Infant Formula: Literature Review on Effects on Growth and the Risk of Developing Atopic Dermatitis in Infants from the General Population. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2018;177(2):123-134. doi:10.1159/000489861. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30001534

- Holvoet S, Nutten S, Dupuis L, et al. Partially Hydrolysed Whey-Based Infant Formula Improves Skin Barrier Function. Nutrients. Sep 4 2021;13(9)doi:10.3390/nu13093113. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34578990

- Chung CS, Yamini S, Trumbo PR. FDA's health claim review: whey-protein partially hydrolyzed infant formula and atopic dermatitis. Pediatrics. Aug 2012;130(2):e408-14. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-0333. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22778306

- Liu X, Yang G, Luo M, et al. Serum vitamin E levels and chronic inflammatory skin diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(12):e0261259. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0261259. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34905558

- Berardesca E, Cameli N. Vitamin E supplementation in inflammatory skin diseases. Dermatologic therapy. Nov 2021;34(6):e15160. doi:10.1111/dth.15160. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34655146

- Jaffary F, Faghihi G, Mokhtarian A, Hosseini SM. Effects of oral vitamin E on treatment of atopic dermatitis: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of research in medical sciences : the official journal of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences . Nov 2015;20(11):1053-7. doi:10.4103/1735-1995.172815. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26941808

- Javanbakht MH, Keshavarz SA, Djalali M, et al. Randomized controlled trial using vitamins E and D supplementation in atopic dermatitis. The Journal of dermatological treatment. Jun 2011;22(3):144-50. doi:10.3109/09546630903578566. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20653487

- Tsoureli-Nikita E, Hercogova J, Lotti T, Menchini G. Evaluation of dietary intake of vitamin E in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: a study of the clinical course and evaluation of the immunoglobulin E serum levels. Int J Dermatol. Mar 2002;41(3):146-50. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01423.x. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12010339

- Panin G, Strumia R, Ursini F. Topical alpha-tocopherol acetate in the bulk phase: eight years of experience in skin treatment. Ann N Y Acad Sci. Dec 2004;1031:443-7. doi:10.1196/annals.1331.069. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15753192

- Patrizi A, Raone B, Neri I, et al. Randomized, controlled, double-blind clinical study evaluating the safety and efficacy of MD2011001 cream in mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis of the face and neck in children, adolescents and adults. The Journal of dermatological treatment. Aug 2016;27(4):346-50. doi:10.3109/09546634.2015.1115814. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26652026

- Teo CWL, Tay SHY, Tey HL, Ung YW, Yap WN. Vitamin E in Atopic Dermatitis: From Preclinical to Clinical Studies. Dermatology. 2021;237(4):553-564. doi:10.1159/000510653. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33070130

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Sleep-wake disorders and dermatology. Clin Dermatol. Jan-Feb 2013;31(1):118-26. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.11.016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23245983

- Rusanova I, Martinez-Ruiz L, Florido J, et al. Protective Effects of Melatonin on the Skin: Future Perspectives. International journal of molecular sciences. Oct 8 2019;20(19)doi:10.3390/ijms20194948. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31597233

- Jaworek AK, Jaworek M, Szafraniec K, Wojas-Pelc A, Szepietowski JC. Melatonin and sleep disorders in patients with severe atopic dermatitis. Postepy dermatologii i alergologii. Oct 2021;38(5):746-751. doi:10.5114/ada.2020.95028. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34849119

- Taghavi Ardakani A, Farrehi M, Sharif MR, et al. The effects of melatonin administration on disease severity and sleep quality in children with atopic dermatitis: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. Dec 2018;29(8):834-840. doi:10.1111/pai.12978. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30160043

- Chang YS, Lin MH, Lee JH, et al. Melatonin Supplementation for Children With Atopic Dermatitis and Sleep Disturbance: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA pediatrics. Jan 2016;170(1):35-42. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3092. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26569624

- Chang YS, Tsai CC, Yang PY, Tang CY, Chiang BL. Topical Melatonin Exerts Immunomodulatory Effect and Improves Dermatitis Severity in a Mouse Model of Atopic Dermatitis. International journal of molecular sciences. Jan 25 2022;23(3)doi:10.3390/ijms23031373. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35163297

- Miles EA, Calder PC. Can Early Omega-3 Fatty Acid Exposure Reduce Risk of Childhood Allergic Disease? Nutrients. Jul 21 2017;9(7)doi:10.3390/nu9070784. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28754005

- Best KP, Gold M, Kennedy D, Martin J, Makrides M. Omega-3 long-chain PUFA intake during pregnancy and allergic disease outcomes in the offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies and randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. Jan 2016;103(1):128-43. doi:10.3945/ajcn.115.111104. http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/103/1/128.full.pdf

- Kremmyda LS, Vlachava M, Noakes PS, Diaper ND, Miles EA, Calder PC. Atopy risk in infants and children in relation to early exposure to fish, oily fish, or long-chain omega-3 fatty acids: a systematic review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. Aug 2011;41(1):36-66. doi:10.1007/s12016-009-8186-2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19997989

- Koch C, Dolle S, Metzger M, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) supplementation in atopic eczema: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. Apr 2008;158(4):786-92. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08430.x. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18241260

- Bjorneboe A, Soyland E, Bjorneboe GE, Rajka G, Drevon CA. Effect of n-3 fatty acid supplement to patients with atopic dermatitis. J Intern Med Suppl. 1989;731:233-6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.1989.tb01462.x. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2650695

- Mayser P, Mayer K, Mahloudjian M, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of n-3 versus n-6 fatty acid-based lipid infusion in atopic dermatitis. JPEN Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition. May-Jun 2002;26(3):151-8. doi:10.1177/0148607102026003151. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12005454

- Gray NA, Dhana A, Stein DJ, Khumalo NP. Zinc and atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. Jun 2019;33(6):1042-1050. doi:10.1111/jdv.15524. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30801794

- Kim JE, Yoo SR, Jeong MG, Ko JY, Ro YS. Hair zinc levels and the efficacy of oral zinc supplementation in patients with atopic dermatitis. Acta dermato-venereologica. Sep 2014;94(5):558-62. doi:10.2340/00015555-1772. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24473704

- Ewing CI, Gibbs AC, Ashcroft C, David TJ. Failure of oral zinc supplementation in atopic eczema. European journal of clinical nutrition. Oct 1991;45(10):507-10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1782922

- Licari A, Ruffinazzi G, M DEF, et al. A starch, glycyrretinic, zinc oxide and bisabolol based cream in the treatment of chronic mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis in children: a three-center, assessor blinded trial. Minerva pediatrica. Dec 2017;69(6):470-475. doi:10.23736/S0026-4946.17.05015-0. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29181960

- Wiegand C, Hipler UC, Boldt S, Strehle J, Wollina U. Skin-protective effects of a zinc oxide-functionalized textile and its relevance for atopic dermatitis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:115-21. doi:10.2147/ccid.s44865. https://www.dovepress.com/getfile.php?fileID=15989

- Aw Yong PY, Islam F, Harith HH, Israf DA, Tan JW, Tham CL. The Potential use of Honey as a Remedy for Allergic Diseases: A Mini Review. Frontiers in pharmacology. 2020;11:599080. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.599080. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33574752

- Alangari AA, Morris K, Lwaleed BA, et al. Honey is potentially effective in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: Clinical and mechanistic studies. Immun Inflamm Dis. Jun 2017;5(2):190-199. doi:10.1002/iid3.153. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28474502

- Al-Waili NS. Topical application of natural honey, beeswax and olive oil mixture for atopic dermatitis or psoriasis: partially controlled, single-blinded study. Complementary therapies in medicine. Dec 2003;11(4):226-34. doi:10.1016/s0965-2299(03)00120-1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15022655

- Vaughn AR, Branum A, Sivamani RK. Effects of Turmeric (Curcuma longa) on Skin Health: A Systematic Review of the Clinical Evidence. Phytother Res. Aug 2016;30(8):1243-64. doi:10.1002/ptr.5640.

- Vollono L, Falconi M, Gaziano R, et al. Potential of Curcumin in Skin Disorders. Nutrients. Sep 10 2019;11(9)doi:10.3390/nu11092169. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31509968

- Togni S, Riva A, Maramaldi G, Cesarone M, Belcaro G. Oral curcumin (Meriva®) reduces symptoms and recurrence rates in subjects with atopic dermatitis. Esperienze Dermatologiche. 2019;21(2-4):42-46. doi:10.23736/S1128-9155.19.00486-2. https://www.minervamedica.it/en/journals/esperienze-dermatologiche/article.php?cod=R50Y2019N02A0042

- Rawal RC, Shah BJ, Jayaraaman AM, Jaiswal V. Clinical evaluation of an Indian polyherbal topical formulation in the management of eczema. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, NY). Jun 2009;15(6):669-72. doi:10.1089/acm.2008.0508. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19480603

- Panahi Y, Sahebkar A, Amiri M, et al. Improvement of sulphur mustard-induced chronic pruritus, quality of life and antioxidant status by curcumin: results of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The British journal of nutrition. Oct 2012;108(7):1272-9. doi:10.1017/S0007114511006544. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22099425

- Shin HS, See HJ, Jung SY, et al. Turmeric (Curcuma longa) attenuates food allergy symptoms by regulating type 1/type 2 helper T cells (Th1/Th2) balance in a mouse model of food allergy. Journal of ethnopharmacology. Dec 4 2015;175:21-9. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.08.038. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26342520

- Sharma S, Sethi GS, Naura AS. Curcumin Ameliorates Ovalbumin-Induced Atopic Dermatitis and Blocks the Progression of Atopic March in Mice. Inflammation. Feb 2020;43(1):358-369. doi:10.1007/s10753-019-01126-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31720988

- Karuppagounder V, Arumugam S, Thandavarayan RA, Sreedhar R, Giridharan VV, Watanabe K. Molecular targets of quercetin with anti-inflammatory properties in atopic dermatitis. Drug discovery today. Apr 2016;21(4):632-9. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2016.02.011. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S135964461630037X

- Jafarinia M, Sadat Hosseini M, Kasiri N, et al. Quercetin with the potential effect on allergic diseases. Allergy, asthma, and clinical immunology : official journal of the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology . 2020;16:36. doi:10.1186/s13223-020-00434-0. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32467711

- Weng Z, Zhang B, Asadi S, et al. Quercetin is more effective than cromolyn in blocking human mast cell cytokine release and inhibits contact dermatitis and photosensitivity in humans. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33805. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033805. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22470478

- Wang K, Jiang H, Li W, Qiang M, Dong T, Li H. Role of Vitamin C in Skin Diseases. Front Physiol. 2018;9:819. doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.00819. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30022952

- Hagel AF, Layritz CM, Hagel WH, et al. Intravenous infusion of ascorbic acid decreases serum histamine concentrations in patients with allergic and non-allergic diseases. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's archives of pharmacology. Sep 2013;386(9):789-93. doi:10.1007/s00210-013-0880-1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23666445

- Vollbracht C, Raithel M, Krick B, Kraft K, Hagel AF. Intravenous vitamin C in the treatment of allergies: an interim subgroup analysis of a long-term observational study. The Journal of international medical research . Sep 2018;46(9):3640-3655. doi:10.1177/0300060518777044. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29950123

- Leveque N, Robin S, Muret P, Mac-Mary S, Makki S, Humbert P. High iron and low ascorbic acid concentrations in the dermis of atopic dermatitis patients. Dermatology. 2003;207(3):261-4. doi:10.1159/000073087. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14571067

- Shin J, Kim YJ, Kwon O, Kim NI, Cho Y. Associations among plasma vitamin C, epidermal ceramide and clinical severity of atopic dermatitis. Nutrition research and practice. Aug 2016;10(4):398-403. doi:10.4162/nrp.2016.10.4.398. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27478546

- Hoppu U, Rinne M, Salo-Vaananen P, Lampi AM, Piironen V, Isolauri E. Vitamin C in breast milk may reduce the risk of atopy in the infant. European journal of clinical nutrition. Jan 2005;59(1):123-8. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602048. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15340369

- Lee JH, Jeon YJ, Choi JH, Kim HY, Kim TY. Effects of VitabridC(12) on Skin Inflammation. Annals of dermatology. Oct 2017;29(5):548-558. doi:10.5021/ad.2017.29.5.548. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28966510

- Roche FC, Harris-Tryon TA. Illuminating the Role of Vitamin A in Skin Innate Immunity and the Skin Microbiome: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. Jan 21 2021;13(2)doi:10.3390/nu13020302. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33494277

- Mihaly J, Gamlieli A, Worm M, Ruhl R. Decreased retinoid concentration and retinoid signalling pathways in human atopic dermatitis. Experimental dermatology. Apr 2011;20(4):326-30. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2010.01225.x. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21410762

- Hiragun M, Hiragun T, Oseto I, et al. Oral administration of beta-carotene or lycopene prevents atopic dermatitis-like dermatitis in HR-1 mice. J Dermatol. Oct 2016;43(10):1188-1192. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13350. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26992660